5 Minutes with… Gabrielle Lyon

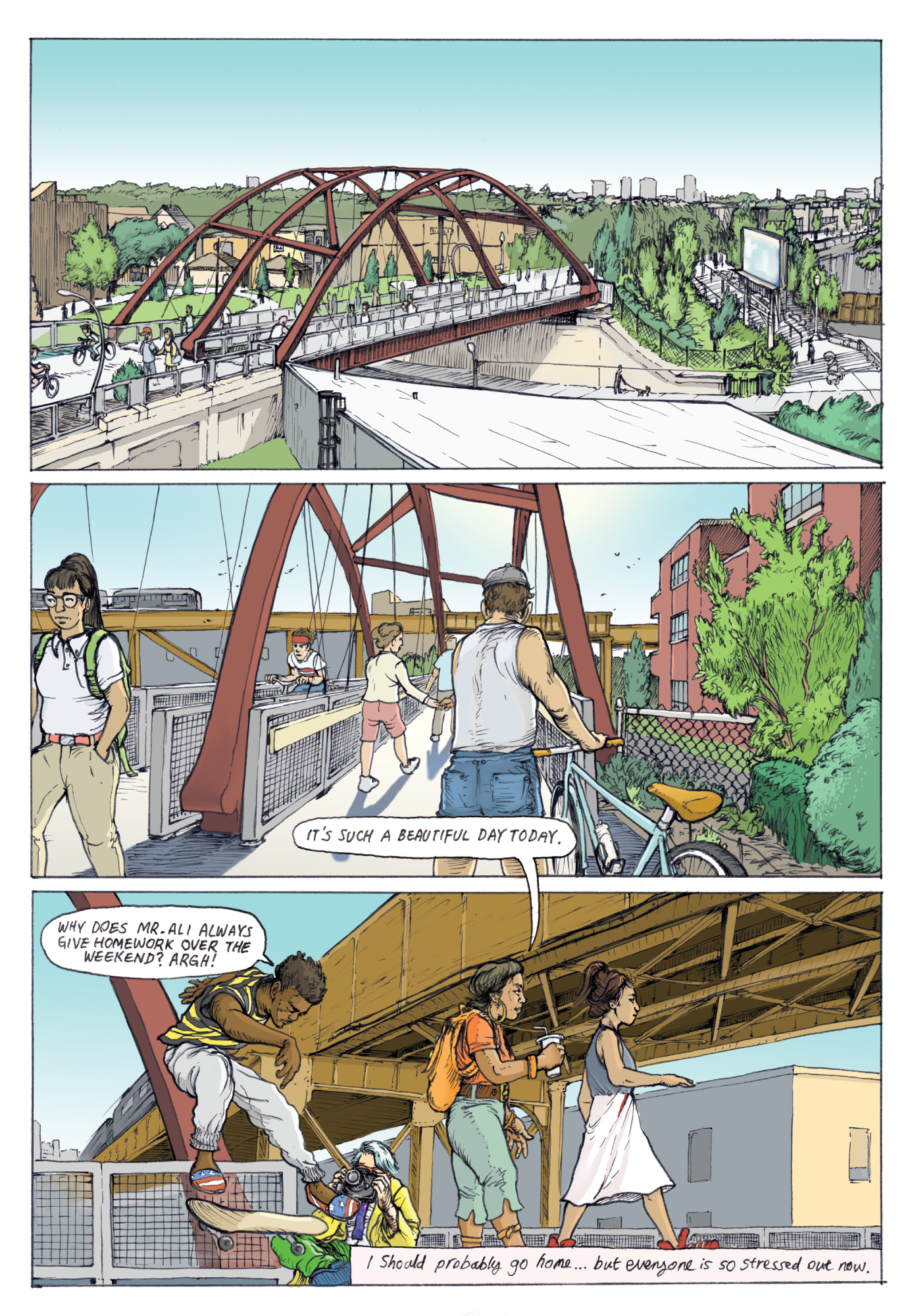

Ahead of the “Make No Small Plans” Wellington event on March 5th, we spoke with lead author and project director Gabrielle Lyon to find out a bit more about her area of expertise, reinventing a 20th century Chicago urban planning textbook as 21st-century graphic novel and her career journey to-date.

What first piqued your interest in urban design and placemaking?

As a child in New Mexico (in the Southwestern United States) I was able to be outside and just walk around by myself in alfalfa fields, along an irrigation ditch, and also on the nearby Native American Pueblo. That experience really imprinted the power of place on me.

As an educator, I have always tried to ensure that the curriculum incorporates the places and spaces in which people live and learn. That said, it wasn’t until I was in my role as the Vice President of Education and Experience at the Chicago Architecture Center that I fully appreciated the power (and politics) of the built environment. In a lot of ways, leading the development of No Small Plans was really my introduction to urban planning.

How did narrative and storytelling in Make No Small Plans ensure the complex concepts of the built environment were accessible to a broad range of readers?

From the outset, I was thinking about No Small Plans as a mass education effort along the lines of the ambitions of the early days of radio. Making something that would be “accessible” to a broad, diverse audience was a primary driver for me. I knew from the beginning I wanted to have high-quality art because I believed good art would really make a difference in the work’s ability to engage readers and catalyze conversations.

The design brief came first; developing the characters and story development came second. I spent about 9 months talking in person with teens, teachers, urban planners, community organizers, architects, and historians. I also convened a day-long design workshop for diverse stakeholders (which New Zealand designer Nick Kapica serendipitously attended!) to explore the question ” What’s most worth knowing and experiencing” when it comes to urban planning and civic engagement?” All of these conversations informed a detailed design brief that I wrote to try to capture what I’d heard in terms of enduring themes and intersecting issues.

The detailed design brief was a key reference when I drafted and announced the commission calling on artists to submit concept drawings that addressed four considerations: “Architecture as a character, Chicago’s past, present and future, youth as having agency, grit, and shine.” (For a while, I thought “Grit and Shine” would be a good title for the book.)

An incredible pool of talent submitted ideas. Ultimately Devin Mawdsley, Kacye Bayer, Chris Lin and Deon Reed (Eyes of the Cat) submitted as a collective and won the commission. As soon I met them I knew they would be the right choice: they are all artists who are also working high school teachers. To me, this meant that not only would the architecture and infrastructure be vividly rendered, but also I had partners who believed in the full capacity of youth. In short, it meant we could create characters that would be authentic.

The team spent a lot of time talking about “Would this really happen? What would teens really do in this situation?” We regularly referred to the design brief to make sure we were integrating the kinds of themes and concepts that people had told me mattered from their perspective. Whenever I wasn’t sure we were on the right track, I would ask the expert – teens themselves. I think all these factors: the diverse input in the early stages, input from teens along the way, and the clear-sighted commitment we had as authors to make something great helped ensure the book would be beautiful as well as multi-dimensional.

Do you have any advice for people designing educational resources for contemporary audiences?

I am a critical pedagogist and social activist. I have an agenda when I design. I think it’s important to understand and appreciate the power and privilege of design and I advocate for designing through an equity lens. Among other things this means I believe it’s important to start with and value of the experiences of the audience themselves.

In my experience – and in the long history of social justice movements, including America’s civil rights movement – focused observations lead to questions, and, in turn, collective questioning is the precursor to social change.

Resources that enable people to see the familiar with “new eyes” can be incredibly powerful – but that doesn’t mean they need to be complex. I believe “real” is usually enough. The real issues in people’s lives contain multitudes, nuances, and humanity. The more grounded in reality you can be the better – even when you’re creating a fantasy like putting teens on a city planning council to make decisions about a public works project.

The act of design itself needs to be intentional. Every line, perspective, building choice in No Small Plans was intentional. We begin the first page of the first chapter (set in the past) from a “bird’s eye view.” The first page of the last chapter (set in the future) begins at street level. These were intentional decisions that make statements about what we believe about who the city should be for.

What were the challenges and triumphs from the project?

I set the agenda for No Small Plans with the operating assumption that life is complicated – I wanted us to embrace the complexity of the issues we were addressing. I didn’t want us to create stories in which teens (or adults) came in with a solution and “saved the day.” Honestly, one of the triumphs was that we completed the project at all. The entire book was written and published in a year. I think the model itself is also a triumph: every book sold enables a book to be distributed for free to a Chicago teen. As of today the book has been given away by the Chicago Architecture Center to nearly 10,000 Chicago youth and is being used in more than 90 schools and a dozen neighborhood organizations. It’s also available to be checked out from every public library in the city. These all feel like triumphs.

What did you learn from undertaking this project?

I changed personally by doing this project; I learned how profoundly transformative collaboration can be from working closely with my coauthors – Devin, Kayce, Deon and Chris. l couldn’t help but learn a lot about the history of planning and the way in which the decisions of a very few people (often designers and/or urban planners) affect the lives of so many people, sometimes for generations. The built environment, for better or worse, can be a long lasting thing. I also learned a lot from teachers. I was reminded and inspired by the incredible creativity of teachers and community organizations who are putting this book to work in hundreds of classrooms and communities. Most of all I learned – yet again – the incredible capacity of young people to have important conversations about what it means to design where they live and learn.

How has the revised visual format of delivery enriched the original content and reading experience? And what has audience feedback been like so far?

Wacker’s Manual was a textbook published in 1911 to promote the 1909 Plan for Chicago through the public school system. Wacker’s manual reproduced many of the 1909 Plan illustrations – it’s basically an urban planning treatise: what are the building blocks of a city, how do they work together, what are the main tenets of the Plan of Chicago. The introduction to the textbook called on readers to understand their role as “future heads of households” and that only through their “united civic efforts” would the city of Chicago be a great city. The Manual became required reading for nearly three decades across the Chicago Public School system.

I didn’t want to “redo” Wacker’s Manual as a graphic novel but I did want to carry forth that Progressive spirit into the 21st century in a genre that feels “right” for this moment.

We did a book release party for Chicago teens in partnership with Mikva Challenge, a civic engagement organization in Chicago. The first question from one of the teens in the audience was “Now that I’ve read the book, I’m wondering what can we do as young people to stop segregation?” If I had any doubts about whether the book would be a success I stopped worrying right then and there.

The response has been very positive. In addition to some terrific reviews, seeing the book “in action” has been incredible. For example, a group of African American teens worked with their local library to make a short documentary film about their neighborhood, Englewood. Their film focused on the places that are special to them. It’s a wonderful tour of the neighborhood and stands in stark contrast to mainstream media portrayals. Another teacher used the book to launch a multi-year project focused on the redevelopment of a closed steel mill on the far southeast side of Chicago. The project turned her students into neighborhood historians who are on a first-name basis with their alderman (the local elected official for their district).

What role can graphic design or illustration play in advancing social/urban change?

Graphic design has been used for promotion and propaganda for a long time for good and evil. Illustration has always been a medium that gives adults and young people a chance to have a shared language to talk about issues that matter that might not otherwise be available, present or allowed.

Sticking with the “good side,” for example, Art Speigleman’s Maus depicts his family’s experience with the Holocaust. Maus is a readable, relatable work of art that engenders empathy. Most importantly it makes an incredibly complex, morose and upsetting topic accessible. There are a lot of people (including myself) who might not otherwise pick up a book about the Holocaust. A second, more recent example, is March, a trilogy about Civil Rights activist, John Lewis. Lewis’ choice to share his personal story through a graphic novel made the context of the movement visible beyond just the short story versions of a handful of characters. Teachers and librarians really embraced it – in large part because youth responded to it.

I love the idea of doing another novel – and most of all using the format to illustrate possible realities – and realities that already exist that people might not otherwise pay attention to: the reality of youth taking action where they live and learn; the reality that we need to equip young people to shape these places and take their roles seriously. But also the reality that we have real questions to deal with as humans: Who is the city for? What’s the relationship between development and displacement? How are decisions made and who gets to make them? What’s my role and my responsibility?

Find out more about No Small Plans here, and to purchase a copy of the graphic novel head here.

Images in this post are reproduced with permission of CAF