Come Together: Design Societies, Professional Associations, Conferences, and Coworking

Written by K. Emma Ng

Supported by Creative New Zealand

Emma Ng is a contributor to Aotearoa Design Thinking 2018, a series of commissioned critical design essays published by Design Assembly and funded by Creative New Zealand.

This article is the third in a four part series on design and its support structures that enable us to nurture, celebrate and critique designers and their work. Over the course of the year Ng will “map Aotearoa’s past and current support structures, look at models elsewhere, and mull possibilities for the future”. Read part one here and two here.

A/D/O’s atrium features a “periscope” skylight and rotating sculptures by architects and artists.

A/D/O’s atrium features a “periscope” skylight and rotating sculptures by architects and artists.

Last year, while living in Brooklyn, New York, I found myself frequenting a new coworking space in Greenpoint called A/D/O. It was strange and slick; a symbolic capstone in a neighborhood made over by Richard Florida-flavoured gentrification. Sponsored by BMW Mini, A/D/O is a “creative space” that combines free coworking desks with paid office spaces and fabrication workshops. It also hosts a Nordic-themed café where I once ate what can only be described as delicious and fancy gruel (mushroom porridge). I worked there because it was free, and because it had nice bathrooms and longer opening hours than the public library.

At the same time, I’d subscribed to a listserv populated by freelance writers and editors. The listserv was the outgrowth of a tiny coworking space in Brooklyn’s Gowanus neighborhood, and it quickly swelled into an active and supportive cohort. As well as sharing leads and advice, writers frequently use the listserv to exchange warnings about media outlets that pay poorly or otherwise mistreat their contributors. Motivated by a general pattern of turbulence in the media landscape, there are even rumblings of the group piloting its own model for a sustainable media organisation.

Weighing these two modes of coworking against one another set me thinking about the potential of these types of spaces — as places where freelancers and contractors might assemble to find a collective voice and eke back some control in their working arrangements. This is an idea we’ll return to later in this piece, after tracing an arc through a range of other initiatives that have pulled designers together: government bodies, professional associations, and design conferences.

My aim is to unravel ideas about how collectivity can support designers, and so it’s important to say from the outset that critiques in this essay are built on an optimistic understanding of “coming together” as an act bursting with potential. And a disclaimer: some of the cultural shifts I’m trying to frame up are relatively recent. So consider this a rough first draft of this history.

Design as an economic lever — state-sponsored initiatives

Let’s start with the most officious mode of collectivity, which sees central government play a role in facilitating design practice. In Aotearoa this has a patchy history. The most prominent state-sponsored design body was the New Zealand Industrial Council (NZIDC), which operated between 1967 and 1988. Following that, not much attention was paid to design until the Design Taskforce was developed in the early 2000s, and quickly succeeded by New Zealand Trade and Enterprise’s Better by Design programme.

I touched on the limited scope of Better by Design in my first article for this series, but here I want to look at how each of these bodies reflects the agenda of their time. Each frames design as a catalyst for economic development. Like Britain’s Design Council, established in 1944, the NZIDC it was initially geared toward boosting trade and commodity production. Design historian Christopher Thompson has written a detailed blog post about the Council and William B. Sutch, the well-known economist and public servant who drove the establishment of the NZIDC. “His contention, his dream you might say,” writes Thompson, “was that a local design promotion body would be a critical element in this intellectually-driven industrial renaissance. In Sutch’s view New Zealand’s future lay with its people and not on the production of grass.”

There is an echo of Sutch’s vision in today’s rhetoric. Like Sutch’s Design Council, Better by Design positions design as an economic lever — albeit involving an evolved conception of design that is poised to serve a knowledge economy. From the outset, Better by Design has sought to instrumentalise design and “design thinking” so that New Zealand companies might thrive in a global market.

These state-sponsored design bodies are not initiatives that have sought to support design in order to develop local artistry and craft for its own sake, or because design is seen as having inherent cultural value. This is illustrated through comparison with contemporary developments elsewhere. In France, for example, at the same time that the NZIDC was being established, the French Ministry for Culture was setting up the ARC — a research and production workshop for contemporary design. Sitting within the Mobilier National, a service agency that cares for historic state and palace furniture, the ARC was intended as an incubator for the country’s leading designers.

Its establishment was driven by the desire of the Minister of Culture, André Malraux, to cultivate a contemporary French style that rivaled the legacy of great eras of French artistry, such as the court of Louis XIV. While Aotearoa’s lack of design history was framed as a positive thing — “a fresh perspective unencumbered by tradition” — by the Design Taskforce in 2003, the French example shows that pride in cultural history can play a big part in driving the ambition of the present.

Pierre Paulin’s Osaka sofa was initially protoyped as part of Mobilier National’s ARC initiative. It was shown at the Universal Exposition in Osaka in 1970, as a representative example of French design.

Pierre Paulin’s Osaka sofa was initially protoyped as part of Mobilier National’s ARC initiative. It was shown at the Universal Exposition in Osaka in 1970, as a representative example of French design.

Postwar enthusiasm — design societies

Prior to the NZIDC, a number of independent societies dedicated to stoking an appreciation for design had popped up in the late 1940s and early 1950s. Powered by driven individuals, these included the Auckland Design Guild, the Visual Arts Association in Dunedin, Wellington’s Architectural Centre, the Christchurch-based Design Association of New Zealand, and the New Zealand Society of Industrial Designers.

These organisations reflected a period of enthusiasm for design that mirrored international developments, but few of these organisations lived out the 1960s. Perhaps the most successful was the Architectural Centre, which is still active today. Based in Wellington, the centre was particularly interested in how modernism could be put to work in the local context.

Alongside manifestos, exhibitions, and political advocacy, the Architectural Centre published a magazine called Design Review, between 1948 and 1952. The two-monthly publication cast a critical eye over a diverse range of design areas, including furniture, urban design, packaging, graphic design, industrial design, and architecture. The impact of the Centre on Wellington’s architectural landscape is the subject of Julia Gatley and Paul Walker’s 2014 book, Vertical Living: The Architectural Centre and the Remaking of Wellington.

The New Zealand Society of Industrial Designers (NZSID) was the only other organisation that survived this period, though its emphasis was different from the outset. The NZSID was conceived as a professional body that represented the interests of designers — design being, at that time, an emerging profession in Aotearoa. In 1991 it merged with the New Zealand Association of Interior Designers to form the Designers Institute of New Zealand (DINZ), which is now the country’s primary membership organisation for designers.

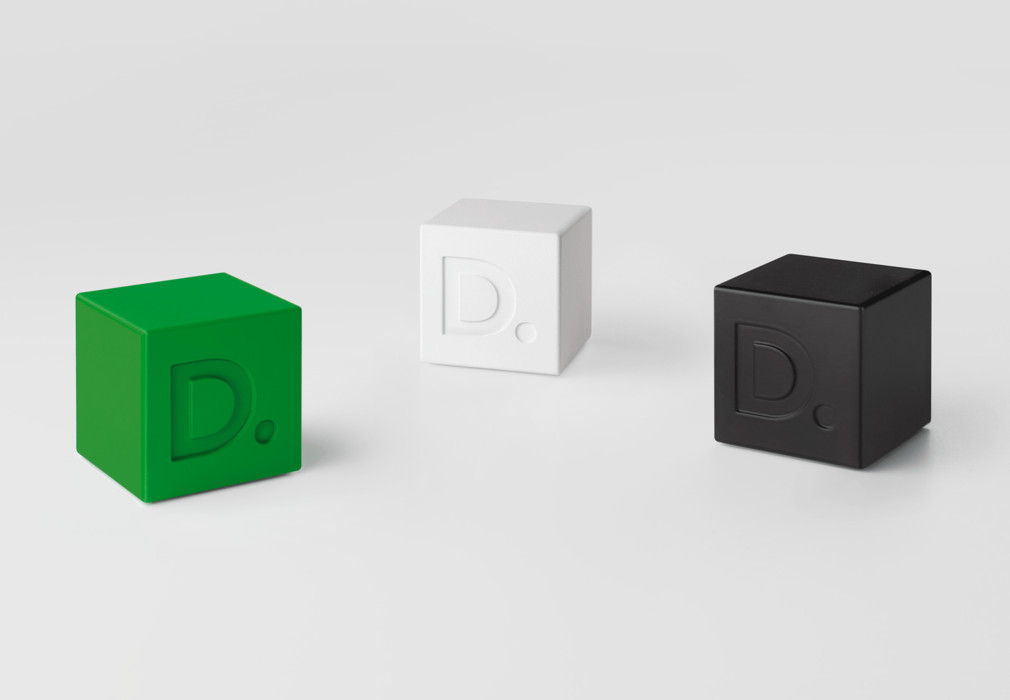

Each DINZ member is sent a green cube to represent their belonging. White and black cubes are awarded as members progress through the ranks.

Each DINZ member is sent a green cube to represent their belonging. White and black cubes are awarded as members progress through the ranks.

Are you being served? Professional associations today

Today DINZ encompasses all areas of design. It is comparable to prominent organisations like the AIGA (American Institute of Graphic Arts) in the United States, and AGDA or the Design Institute in Australia. Professional bodies like these might be considered to have the following functions:

- Looking out for the interests of their members.

- Providing resources, training, and development opportunities to both build business capacity and help advance the discipline.

- Advocacy — Developing the reputation of the discipline and voicing a collective position.

The annual Best Awards is DINZ’s most high-profile initiative. Described as “Australasia’s largest annual showcase of excellence across graphic, spatial, product, interactive and motion design,” the awards attract in excess of 1000 entries per year. Year on year they build an archive of what is considered the top design practice of the moment. In celebrating the work of Aotearoa’s designers, the Best Awards have become an eagerly anticipated institution.

But beyond the Best Awards, it would be valuable if there was a forum — managed by DINZ or another organisation — to address emerging thematic concerns to do with the discipline and its workforce. For instance, the programmes of AIGA in the United States currently include initiatives dedicated to developing design’s engagement with social change, workforce diversity, and female leadership.

In Aotearoa, there is room for greater vision and leadership on these issues in relation to design. For instance, gender equity has been the subject of much discussion in the fields of architecture and engineering, producing initiatives such as The Diversity Agenda in Aotearoa and Parlour in Australia. Yet of the 42 Black Pins that have been awarded at the Best Awards, only 3 awardees have not been men. The Black Pin is the highest honour, forming a canon of figures considered significant in Aotearoa’s design history. A national design organisation like DINZ should lead the way in exploring the reasons for this disparity, and whether they’re still impacting the design industry today.

In-house designers, those employed at design agencies, and freelancers all face different challenges. Freelancers, in particular, lack the avenues to address workplace issues — which can be as diverse as mental health, employment protections, or software subscriptions. And in Aotearoa, as elsewhere, the trend is toward a growing contingent workforce. An active membership organisation could support this group, meeting pragmatic needs as well as fueling the creative ambitions of the discipline. As the freelance workforce grows, the value of a collective body that can advocate for the discipline also becomes greater. As a model, we could look to the New Zealand Institute of Architects (NZIA). They are active in providing comment on media stories, writing submissions, and advancing the public understanding of architecture through their Festival of Architecture.

Design Enters the Mainstream — Design Conferences

Perhaps conventional membership organisations are no longer the natural forums we turn to, to discuss these challenges, come together, and look to the future. Conferences and coworking spaces are evolving into multi-faceted platforms that support activities like journals and year-round event programs. Could sturdy support structures develop out of these alternative modes of collectivity?

Design conferences range from the specific (e.g. the 2011 typography symposium Typeshed 11) to the broad (e.g. Festival for the Future, pitched at “emerging creatives, entrepreneurs and leaders”). The most notable is Semi Permanent, a multidisciplinary design conference that began in Australia in 2003. The first New Zealand iteration was held in Auckland in 2004. The conference has always featured an enticing mix of international stars and local talent and welcomed the attendance of non-designers such as students.

One slide “takeaways” — the bread and butter of Semi Permanent.

One slide “takeaways” — the bread and butter of Semi Permanent.

Perhaps Semi Permanent’s success can partly be attributed to this widely-pitched audience and its broadening into a wider conception of the “creative industry” — one accompanied by appealing narratives of empowerment and entrepreneurship. Looking back, Semi Permanent emerged at a particular moment, where talking and knowing about designing — being a kind of design consumer or design connoisseur — was popular and mainstream in a way it perhaps hadn’t been before.

This was a time when you might still have been able to get a shady version of the Adobe Suite, and a new era in which people were growing up with computers — which meant that young people were playing on computers. The popular social media platforms of the time, MySpace and Bebo, both encouraged users to customise the appearance of their profiles — providing yet another sandbox for experimentation with elements of design and coding.

It was also around this time that Gary Hustwit’s documentary Helvetica (2007) came out — a movie about design that appealed to a general audience by showing just how ubiquitous one typeface was in the world around them. Reflecting on its release Hustwit has said, “At the same time, that was really, really when fonts became more of a kind of mass culture thing. My mom knew what a font was suddenly. Ten years before that in the 90s, people didn’t. It was only a thing if you were in the trade or you were in design. It was just that moment when people were becoming interested in fonts and using them all the time online.”

Reflecting this general broadening, the way Semi Permanent articulated its purpose evolved sometime around 2016, as it became a “three-pronged platform: design, business, and culture.”

Danny van den Dungen of Experimental Jetset, being interviewed for the documentary Helvetica.

Danny van den Dungen of Experimental Jetset, being interviewed for the documentary Helvetica.

Coworking

This period of recent history has also seen the emergence of coworking as a response to an expanding itinerant workforce. Internationally WeWork is the big player; locally we have the BizDojo, and a number of smaller independent coworking spaces. These coworking spaces see individuals and businesses brought together in a kind of flexible proximity, promising not just workspace, but also a collegial environment.

It is easy to be cynical of companies like WeWork, which sometimes seems to be hawking a cultivated idea of community in pursuit of global domination. If coworking spaces are community centers, they are often ones carefully tailored to targeted consumer groups. For example, while A/D/O declared itself “open to all,” there’s no doubt that the space’s Instagram-readiness — set against a backdrop of vanishing light industry (A/D/O was itself a converted warehouse) and rising property values in the area — put out signals about who this particular community center aimed to welcome. I’m thinking also of lifestyle clubs (within which workspace is one of many benefits) like New York’s women-only club The Wing, which packages elite membership in millennial shades of female empowerment.

But coworking is not inherently beholden to the moral compass of startup capitalism. The listserv I mentioned earlier is one example of how working alongside one another (physically or digitally) can be a springboard for support, development, and even grassroots endeavours to change a discipline’s working conditions. Locally, the Enspiral network has been modelling one way that people can be brought together in working arrangements under a guiding mission that prioritises particular values.

Bringing it all together

In recent years, Semi Permanent has begun to include panel discussions in their programs. There’s opportunity there to follow AIGA’s lead and include programming that not only feeds designers’ creative development, but also other aspects of their wellbeing. And just as Semi Permanent has evolved from a “conference” into a “platform,” coworking spaces frequently run event programmes. The different modes of coming/being together discussed in this piece have begun to overlap more and more. Though their bounds for entry are more porous than traditional membership bodies — perhaps you only attend one event — these are spaces that have begun to address the emerging needs of those they bring together.

In bringing people together, coworking spaces and conferences are platforms that can act as catalysts for designers to drive the changes they want to see within the discipline. Where the function may have previously been assigned to membership organisations, they are spaces filling the gaps in new ways, and spaces for us all to ask the question: What is the future we want for design in Aotearoa, and how can we take steps to get there?