Showing, Sharing, and Beyond: Design Exhibitions in Aotearoa

Written by K. Emma Ng

Supported by Creative New Zealand

Emma Ng is a contributor to Aotearoa Design Thinking 2018, a series of commissioned critical design essays published by Design Assembly and funded by Creative New Zealand.

This article is the second in a four part series on design and its support structures that enable us to nurture, celebrate and critique designers and their work. Over the course of the year Ng will “map Aotearoa’s past and current support structures, look at models elsewhere, and mull possibilities for the future”. Read part one here.

Installation view of MoMA’s first design exhibition, Machine Art (1934). The Museum of Modern Art Archives.

Installation view of MoMA’s first design exhibition, Machine Art (1934). The Museum of Modern Art Archives.

In 1934, just five years after its opening, New York’s Museum of Modern Art staged its first design exhibition, titled Machine Art. Pristine glass beakers stood to attention alongside gleaming steel saucepans and other mass-produced objects. Illuminated by the gallery lighting, they cast shadows on the walls; sharp-edged silhouettes of industrial modernity. Curator Philip Johnson “took unusual steps to show the objects to their greatest effect,” MoMA writes, “he screened the walls and ceilings of the Museum’s second location in a 19th-century brownstone in order to hide its decorative molding, creating a sleek, clean atmosphere that set a new standard for the display of design objects.”

Almost 85-years later, many design exhibitions still emulate this standard. Objectspace, Aotearoa’s only institution dedicated to exhibiting design, reopened in Auckland last July with an expanded mission that brings architecture into the fold alongside craft and design. Housed in a converted industrial warehouse, the new gallery’s four exhibition spaces are sleek and square — right down to the grid suspended over the gallery to support lighting and hanging displays. The gallery’s reincarnation in this larger, purpose-built space is a triumphant achievement made possible by significantly increased funding and years of mahi by the gallery’s founding director, Phillip Clarke, and his successor, Kim Paton. As anyone who has kicked around in institutions operating in similar (Creative New Zealand-dependent) conditions in Aotearoa knows, such opportunities to scale up are rare and hard-won.

The move hints at grander ambitions for the institution; perhaps even a slow trajectory towards being our national museum for craft, design, and architecture. Though still a distant horizon, this has begun to seem possible because the gallery’s inclusion of architecture brings with it new sources of revenue. Unlike artists and craft practitioners, who tend to be accompanied by meagre funding, architects operate in a splashier commercial sphere. Paton has worked with Brown Bread, who specialise in helping arts institutions with philanthropy and partnerships, to reel in support from architecture firms and studios and shore up these new foundations for Objectspace. Alongside doubled investment from Creative New Zealand (secured by Clarke, in return for Objectspace officially taking up a national leadership role in the craft/object sector), a significant chunk of Objectspace 2.0’s opening and early programming has been underwritten by pro-bono work from RTA Studio, support from lead partner Ockham Residential, and a list of other studios and design companies such as Formway and Fisher & Paykel.

The gallery’s success hinges on its ability to make the case for exhibiting design, craft, and architecture to potential supporters and audiences. Typically when new institutions open, they generate PR-style coverage — Objectspace has attracted plenty — in the form of profiles and blurbs in industry mags and glossy weekend supplements. Meanwhile, kanohi ki te kanohi, we pick over the details of their debut, weighing up all the minor successes and stumbles (perhaps we have the crit-oriented educations offered by our design, architecture, and art schools to thank for this readiness to critique).

But it also feels important to give achievements like Objectspace’s expansion their due by taking a moment to outline the sense of possibility that comes with it, and to consider how the gallery might respond to a changing discipline and the gaps left by other institutions’ design programming. It’s impossible to fairly judge Objectspace by the merits of its first year of exhibitions in the new space. There is such a paucity of consistent exhibition practices for design and architecture in Aotearoa that it will take time for new modes of critical practice to develop, as designers recognise that there is an outlet for the reflexive types of work that the exhibition format can accommodate.

Design has always been included in Objectspace’s exhibition program. The most recent exhibition hosted in their main gallery is a typical example. Curated by design historian Michael Smythe and sponsored by Fisher & Paykel, the show explored the work of industrial designer Peter Haythornthwaite — who, among many other things, designed the ubiquitous kiwifruit knife-spoon for Zespri. Industrial design, graphic design, and fashion design are all represented in Objectspace’s archive, and past shows at the Ponsonby Road space include exhibitions like Au Revoir Marilyn Sainty (2005), Printing Types: NZ Design since 1870 (2009) and Mark Cleverly: Master of Craft (2014). The gallery also has a long history of supporting emerging practice, particularly through their annual showcase of work by recent graduates.

Zespri has been working to produce a more environmentally friendly version of the knife-spoon designed by Peter Haythornthwaite.

But the new building, with its larger footprint and four varied spaces (which can be combined or separated as needed), offers the opportunity to exhibit even more design, and a greater variety of design exhibitions. Paton has indicated this is the intention, saying that until now Objectspace “has done the most work in the field of craft. The focus is to grow that commitment in design and architecture to what will become three key pillars of the work that we do. It is a logical progression.”

Elsewhere, visual and material culture is abundant in our museum collections, but they tend to be acquired and exhibited with priority given to their social significance rather than their design value. Design-focused exhibitions in Aotearoa are relatively rare — especially graphic design — and usually have a historic focus.

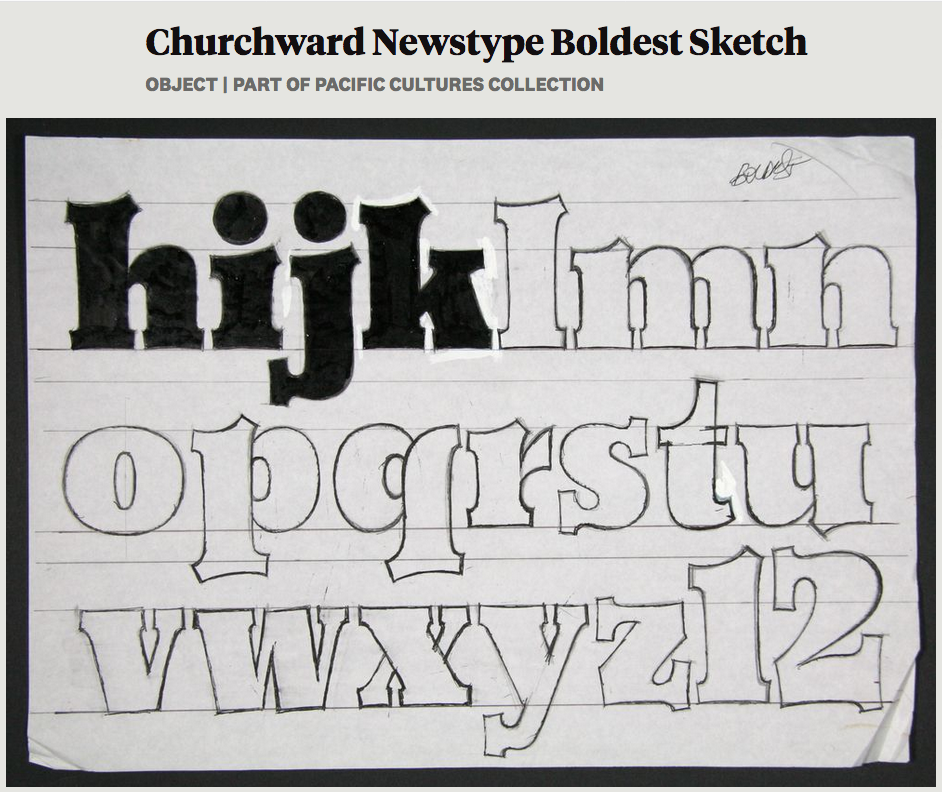

One telling example is the 2008 Te Papa exhibition Letter Man: Joseph Churchward’s world of type. Joseph Churchward is a significant figure in Aotearoa’s design history but this exhibition of Churchward’s work was actually developed by curators Safua Akeli and Sean Mallon for Te Papa’s Pasifika programming. Akeli has written of how this relatively modest exhibition, which was created to complement the then-newly opened Tangata o le Moana long-term displays, represented a significant development in the museum’s approach to building and exhibiting its Pacific collections — shifting from an ethnographic focus to a biographic one. If it were not for Akeli and Mallon’s sharp curating — their strides in ensuring that Te Papa’s Pacific collections have contemporary relevance — the work of this prolific international practitioner may not have been exhibited. In concert with the exhibition, Te Papa acquired a huge number of samples of Churchward’s work, but they remain among the only typography collected by our national museum.

One of the Joseph Churchward sketches held by Te Papa — as part of the Pacific Cultures Collection.

One of the Joseph Churchward sketches held by Te Papa — as part of the Pacific Cultures Collection.

Art galleries have also provided a venue for some exhibitions that engage with design histories, both local and international, including California Design, 1930-1965 at Auckland Art Gallery (2013), The Adam Art Gallery’s We Will Work with You (2013), Play: International Design for Children at The Dowse Art Museum (2013), City Gallery Wellington’s A Mobile Library (2011-12) and Churchward Samoa (2014), and projects like Simon Denny and Michael Stevenson’s works for the Venice Biennale (Secret Power and This is Trekka, respectively). But the historical bent of these projects, and their tendency toward being either highly idiosyncratic or a sweeping survey, leaves a lot of room for locally relevant exhibitions driven by contemporary practice — a gap that Objectspace is poised to fill.

The collaboration between New Zealand type designer Kris Sowersby (KlimType Foundry) and Alt Group that was included in Objectspace’s opening lineup is a promising glimpse of what might come. The mini-exhibition featured the typefaces Untitled Sans and Untitled Serif, which were an experiment in designing a “neutral typeface,” absent of both the typographer’s hand and the cultural references that other typefaces are laden with. It’s an exhibition that allows us to share in the concerns of a working designer like Sowersby, without the need to be justified by biography or art — it’s an exhibition of typography through the lens of type design.

Objectspace also has the opportunity to stage thematic exhibitions that explore how design mediates the world around us — contemporary exhibitions that do not focus on a single designer. Paton has said, “We’re learning how to get good at asking people to support us and work with us if they see merit and value in what we do, not because its a nice to have, or because we are deserving, but because art, design and creative-making practices are essential, for culture, for social well-being and to the economy.” This mirrors the changes taking place in design exhibitions and museums around the world. Endless parades of expensive chairs no longer dominate, as institutions instead look to demonstrate the essential relevance of design to society and culture.

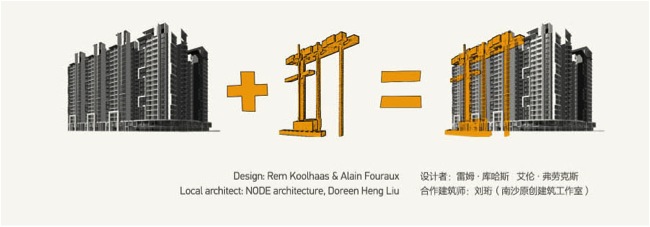

This is reflected in new ways of both exhibiting and collecting design. New York’s Cooper Hewitt has pioneered interactive and immersive ways to experience the museum. The Times Museum in Guangzhou is embedded in an apartment building, setting the scene for the museum’s unique engagement with questions around urban development and the politics of everyday life. And the Design Museum in London, which reopened in 2016, features an introductory exhibition called Designer Maker User, emphasising the relationship between the three roles, unlike conventional design exhibitions that have tended to overemphasise the designer.

The Times Museum occupies the 19th floor and lobby of a residential apartment building, joined by elevator shafts.

The most influential player is perhaps still the Museum of Modern Art in New York, as led by Paola Antonelli, the architecture and design department’s senior curator. When MoMA added the “@” symbol to its design collection in 2010, Antonelli, wrote of how it demonstrated that objects no longer needed to be physically possessed in order to be acquired, freeing curators to “tag the world and acknowledge things that ‘cannot be had’—because they are too big… or because they are in the air and belong to everybody and no one.” This loosening of what it means to collect and curate makes sense; curators have shifted from being the caretakers of objects to an expanded role as arbiters of ideas.

We often talk about how curating has been diffused into a general activity enjoyed by anyone with an Instagram account, with the term used as a synonym for any act of selection. But MoMA’s acquisition of the “@” symbol is evidence that not only has curating seeped out of the museum, but museums and the practice of curating are at the same time being shaped by digital ways of being. Antonelli’s description of the acquisition as a kind of “tagging” is an obvious marker of this. Tagging is an activity made commonplace by computers. Blogs, social media, and databases all rely on tag systems. Pinterest and Tumblr all operate as tools for tagging — allowing us to lay claim to something, categorise it and mark it as significant — without the need for ownership. Interfaces for library, museum, and archive collections increasingly offer this same function, allowing us to curate our own digital mini collections from their holdings.

Tagging opens up the world as one giant collection to be curated, freeing galleries like Objectspace (which has no collection) to nimbly respond to the specifics of our time and place, rather than working within the limits of an inherited set of objects and museological practices. Kim Paton has expressed a desire for the new Objectspace to help build our shared vocabulary for talking about design issues that affect us every day — these issues might include things like how social media shapes how we receive information or bike lanes in Tāmaki Makaurau. With design pressing in on us from all sides, design museums and galleries can play an important part in growing our awareness of, and encouraging us to talk about, the impacts of the things we design and make.

My first ever writing commission was for The Lab, a project that was part of If you were to live here… the 5th Auckland Triennial, curated by Chinese curator Hou Hanru. The Lab was located on the top floor of the Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki and hosted four student-driven architecture projects over the course of the Triennial. I was involved in “Ideal Home(land)”, led by Sarosh Mulla (who incidentally, is one of the two architects from PAC studio who have developed Objectspace’s next exhibition, Penumbral Reflections). I still think of the project often because of the ongoing relevance of its topic — housing and NIMBYism in Auckland — but also because it was an exhibition that centered design questions and sought to engage the public. Hanru described the Lab as “the brain, the intellectual core of the Triennial. As a kind of open university, its programme — case studies, lectures, presentations, symposiums, panel discussions, performances and outside excursions — will unfold during the duration of the Triennial.”

Ideal Home(land) in The Lab. The Lab’s fit-out was designed by Sara Lee from unused fixtures in the Auckland Art Gallery storeroom such as crates and frames. It could be rearranged to suit the needs of each project.

Ideal Home(land) in The Lab. The Lab’s fit-out was designed by Sara Lee from unused fixtures in the Auckland Art Gallery storeroom such as crates and frames. It could be rearranged to suit the needs of each project.

I admired The Lab because it attempted to shape a design exhibition in a way that was open and responsive (mirroring the “educational turn” seen in art exhibitions). In developing their own interpretation of what a support structure might be, the artists Céline Condorelli and Gavin Wade have suggested it could be: “a space which is continually reinvented by its users in relation to its context.” Though they weren’t talking about design or museums, it’s a statement that conjures up all sorts of imaginative possibilities for what a design exhibition could be. Design museums should strive for continual reinvention because unlike art, exhibitions have never been the given format for showing and sharing design — even truer now that our lives are lived digitally as well as physically.

Reinvention is a challenge, but also an opportunity to reshape the institution — to let old ways of doing things seep out of it to be replaced by new learnings from outside. Tagging, as a mode of curating, not only frees up institutions to address the wider world, but also frees up curating, loosening it from the museum’s grip of power and allowing people outside of the institution to curate themselves into the conversation. The challenge for museums is to figure out remain relevant and useful, not the other way around.

With Objectspace’s reopening, the time is ripe to think broadly about what design exhibitions can contribute to design practice in Aotearoa and to our understanding of design’s role in culture and society. But just as the title of MoMA’s 1934 exhibition, “Machine Art,” introduced the unfamiliar by adjoining it to the familiar, now is also the time to try new some new things and leave some old things behind.