Puncturing Mythology: Looking beyond the shiny myths that distract from the complexity in design in Aotearoa

Written by K. Emma Ng

Supported by Creative New Zealand

Emma Ng is a contributor to Aotearoa Design Thinking 2018, a series of commissioned critical design essays published by Design Assembly and funded by Creative New Zealand.

This article is the first in a four part series on design and its support structures that enable us to nurture, celebrate and critique designers and their work. Over the course of the year Ng will “map Aotearoa’s past and current support structures, look at models elsewhere, and mull possibilities for the future”.

“The National Grid does away with catch-all mythologies about design in favour of something that’s closer to the truth — design isn’t sacred, more borrowed than new, it isn’t always great and sometimes it’s terrible.”

— Kim Paton, The National Grid #8

Design has always been susceptible to mythology. At least since Raymond Loewy featured on the cover of Time magazine in 1949, design has bedazzled its own narrative with sparkly heroes. In its pursuit of the contemporary, design soaks up trends and buzzwords, becoming waterlogged with empty platitudes and bloated ego.

Sometimes even hopeful ideas fall victim to bad veneers. When Rocket Lab launched Aotearoa’s first satellite in January, the technological achievement was eclipsed by the company’s own narrative overreach. The satellite was dressed up in a shiny shell and pumped up with the hot air of aspirational universalism, described by the company as “a bright symbol and reminder to all on Earth about our fragile place in the universe.” The cosmos is supremely hospitable to mythology.

Frontmen: Raymond Loewy on the cover of Time Magazine (1949) and Rocket Lab founder Peter Beck with the Humanity Star (2018).

Frontmen: Raymond Loewy on the cover of Time Magazine (1949) and Rocket Lab founder Peter Beck with the Humanity Star (2018).

Mythology is reassuring and enticing. But the four articles that I’ll be contributing to the 2018 Aotearoa Design Thinking series will leave mythology behind, searching instead for its opposite. Rather than reaching for the stars, we’ll be on the ground, looking at the support structures that lay the foundations for design practice here. Instead of heroes, my subjects will be the bit players and stagehands that can help cultivate a thriving design culture.

By support structures, I mean the professional bodies, publications, conferences, archives, workshops, scholarship, exhibitions, and other designer-run initiatives that provide opportunities for us to celebrate, critique, and nurture designers and their work. Over the course of the year we’ll map Aotearoa’s past and current support structures, look at models elsewhere, and mull possibilities for the future.

A solar system might be a better metaphor for the way these activities interact — some of them sitting comfortably within the asteroid belt of “design practice,” others of them outside — with concentric and overlapping orbit paths that bring these activities into or away from each other at different times.

Activities carried out “through” and “around” design in Aotearoa.

Activities carried out “through” and “around” design in Aotearoa.

But first, the argument for thinking about and investing in these activities:

Aotearoa could do better by its designers. The nation’s biggest design competition in recent history was a disaster. I’m sure few of us want to revisit the 2015-16 New Zealand flag referendums — no matter whether you were for, or against change — but the saga is compelling as an illustration of just how misunderstood and undervalued the work of designers can be.

To quickly, painfully, rehash:

Ideas for a new national flag were crowdsourced from the general public; a 12-person panel, with nary a designer (or vexillologist) on it, was tasked with shortlisting the entries; the list was littered with Hundertwasser rip-offs (later withdrawn due to copyright violation), Gordon Walters (re-)appropriations, and symbols worn out by their day jobs as NZTE and sports team logos; and the process was hindered by a general lack of public interest — culminating in voters electing to keep the existing flag. No change, at a cost of $25.725 million.

The top 40 alternative flag designs.

The top 40 alternative flag designs.

Looking through publicly available records, the neglect of professional design expertise from the process is stark. Early meeting notes show a small “due diligence” window of less than a week was planned to hear from a focus group that might include designers — but this was to take place only after the panel had whittled down the designs from more than 10,000 entries to their preferred 15 (the shortlist eventually included 40 designs). The feedback the panel sought at this stage was “technical, not subjective” comment, limited to flagging grave issues. Never mind that within the design process, these two types of knowledge are often contingent and deeply intertwined.

Crowdsourcing, which is spec work in another guise, has been widely pilloried as a design strategy — both for undercutting the professionalism of the design industry by asking a large number of people to undertake the design process as unpaid work, and for producing poor results for the client because it cuts out the part where the designer closely engages with them to understand their needs.

I’m revisiting the failed flag design process not for the thrill of schadenfreude, but because I think it says something deeply tragic about the value we place on designers that an official process built to facilitate an identity redesign (the primary purpose of the whole exercise was design!) could neglect design professionals so brazenly. There are alternative ways that public engagement could’ve been made fundamental to the process, without also compromising design expertise.

The decision to use crowdsourcing to drive a government-initiated design process reflects a general lack of understanding about the work that designers do and their contribution to everyday and civic life. As all designers know, design is only sometimes an ornamental practice. Public engagement guidelines drafted by the flag referendum panel emphasised the need to “Lift the conversation from how the flag looks to what it can say about our country.” But designers understand that these two things are inseparable — what you’re saying cannot be divorced from how you say it. Design is a language, and like any language it can be used eloquently and it can be used coarsely. Its style and voice can be modulated to communicate different messages. It can be funny, crude, distant, earnest, and ironic. Design is a manner of speaking.

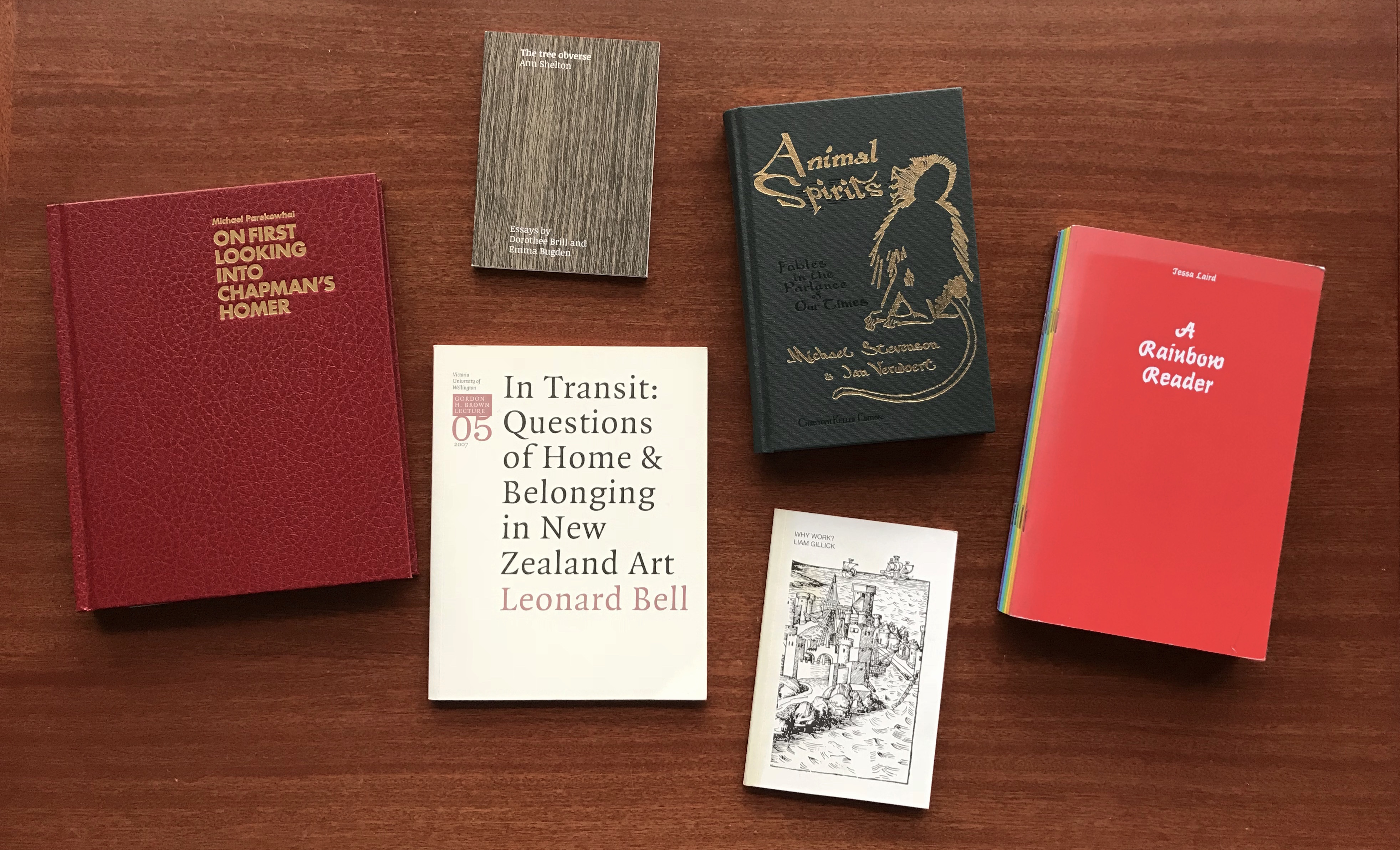

cover designs for art books, mostly from Aotearoa.

cover designs for art books, mostly from Aotearoa.

So, how can we bolster our design culture and the value we place on designers?

I think it’s essential to encourage a rich variety of “opportunities for us to celebrate, critique, and nurture designers and their work,” as I phrased it earlier. And throughout this series we’ll look at different activities in depth, surveying their impact on past and present design practice in Aotearoa, and exploring our capacity for strengthening these opportunities.

But I also want to suggest that we need to puncture design’s mythology in order to be able to share its true value with a wider audience. Here are couple of myths we could start with:

Myth #1 — The role of designers is to produce designer objects

Good design doesn’t always make the heart race or wear a fashionable coat. Collectively — and I’m speaking now not just about an audience of designers but a wider one — we need room to celebrate design that isn’t flashy, as well as to critique empty razzle-dazzle. In the quoted passage from Kim Paton, now the director of Objectspace, that opens this essay, she goes on to describe design “as a verb […] constantly in action and importantly not separated from life.” We need to give the quotidian its due, building greater appreciation for the role of design even when it is, as Kim Paton says, inseparable from life itself.

If you’re reading this, you’re probably already interested in design. But try to recall the type of design books that are stocked in your nearest Whitcoulls or Paper Plus. What kind of story do these publications tell about design? What mythology do they uphold?

Looking at the selection available at one local bookseller, there are a few formats that dominate:

- Monographs exalting a single designer as exceptional (e.g. Gifford Jackson: New Zealand Industrial Design Pathfinder or Art of Impossible: the Bang & Olufsen Design Story).

- Books that profile exemplary examples in a particular category, often like a book version of a listicle (e.g. 40 Legends of NZ Design, 1000 Chairs, Coverup: The Art of the Book Cover in New Zealand, or 100 Best Bikes).

- Books that (concerningly) claim to summarise the entire history of design (e.g. Design: the Whole Story or Design: the Definitive Visual History), usually illustrated with a parade of examples.

Popular design histories around the world, ours included, tend to be presented as timelines of remarkable people and objects, inheriting the canonical mode that factions of art history — design history’s older sibling — have been trying to unpick in recent decades. Many of these are excellent books that tell important stories and flesh out our understanding of the upper echelons of design practice. But the canonical model can be particularly detrimental when it comes to design, because celebrating exceptional examples reinforces a distinction between “designer” objects and everything else. It creates the misconception that designers are in the business of making good looking and expensive objects — set dressing for an aspirational lifestyle that is out of reach for most of us. In reality, both a designer chair and a chair are designed objects. Everyday objects are also part of the story of design, and we need to recognise the role that designers play in shaping the everyday world we all inhabit.

Myth #2 — Nationalism and Nostalgia

So, if design isn’t just an elite practice, what’s our current conception of popular design in Aotearoa? I would say that the lens through which we regard popular design history is foggy with nationalism and nostalgia, which I think is particularly limiting. I worked in the shop at Te Papa for a few years and saw first-hand just how effectively Aotearoa’s popular design history is strong-armed into a singular narrative about what our national identity looks like. For the most part, our trade was the supply of a colourful and upbeat array of “iconic” imagery — perennial and apolitical — to meet seemingly endless demand from both domestic and international customers.

Calcified mythology: New Zealand Post’s 1994 Kiwiana stamps.

Calcified mythology: New Zealand Post’s 1994 Kiwiana stamps.

To me, one measure of a strong design culture is the diversity and nuance of the design stories being told to the widest possible audience (in addition, of course, to layers of expert discourse being exchanged within design spheres). While Kiwiana has played an important role in establishing the sense that we do have a unique culture that’s worth cherishing, in no way does it convincingly cover the diversity of design in Aotearoa. As a set of symbols from our shared visual and material archive, Kiwiana might be presented as apolitical — as icons that unify all New Zealanders — but in fact it is highly political, in that it identifies a limited range of cultural identities as nationally significant. The answer for how to strengthen Aotearoa’s design culture should lie in expanding our reference points, not fortifying a singular narrative that becomes more flattened, more iconic, with each telling.

Kiwiana’s skew towards a down-home conception of New Zealand identity has also produced another myth that perhaps limits our ability to value the work that designers do: the “No. 8 Wire”, “she’ll be right” attitude — the idea that great Kiwi inventions spring from an ad-hoc process of blokes working in sheds. I wonder if this inherent belief in the capability of the Kiwi “everyman” as a designer is what allows professional design expertise to be fundamentally excluded from a process like the redesign of the New Zealand flag.

No need for design school: these design guidelines were provided to entrants and used by the panel to make their assessments. (The guidelines have been abridged for publication here).

No need for design school: these design guidelines were provided to entrants and used by the panel to make their assessments. (The guidelines have been abridged for publication here).

Mythbusting — Expanding the way we talk about design

We need to talk about a wide variety of design activity and we need a culture that accommodates a range of ways of thinking and talking about design.

Others have made similar arguments. In a book about the designer Mark Cleverly, published by Objectspace in 2014, the editor Jonty Valentine makes an effort to demonstrate how even a single publication can accommodate different modes of talking about design. Cleverly distinguishes between the “design value” and “historical value” that might be drawn out of a single subject by different interrogators (designers and non-designers), and Valentine makes a point of highlighting his own bias (meant in non-perjorative sense) as “a graphic-design writer” — perhaps to encourage others undertaking design research and writing to be similarly specific, even idiosyncratic, in their approach.

In The National Grid #6, Luke Wood and Noel Waite talk about how much of Aotearoa’s design history still needs to be pulled out from the private sphere and made known to a wider public sphere. In comparing the different approaches to processing primary sources that have been taken by them and by designer-authors like David Bennewith and Hamish Thompson, they seem to agree that a diversity of approaches to design history is a good thing, particularly when working against a generally “narrowed conception of design.”

Luke Wood, quoting correspondence with Noel Waite in The National Grid #6.

Luke Wood, quoting correspondence with Noel Waite in The National Grid #6.

Underpinning their conversation is the idea that not only can the practice of history be used to understand design, but design itself might be enacted as its own research process to help us come to understand culture at large — a critical practice of talking about and through design that is more expansive than “design history” (“design history” acting as an quickly understood label for this more nebulous activity).

This expanded, critical conception of design is fundamentally different to the role afforded to design practice in Aotearoa by government agencies, which places design in relation to entrepreneurship — with officially sanctioned initiatives being perhaps another diagnostic for Aotearoa’s design culture.

The Official Myths — Design as an economic tool and nation-building exercise

The National Grid, which is a project co-authored by Wood and Valentine, quite consciously positioned itself in counterpoint to a report produced by the Design Taskforce, which was established in 2003 by a Labour government. The initiative has since evolved into the Better by Design programme managed by NZTE, and is dedicated to introducing design thinking to export businesses. It regards design as a capitalist tool, seeing the practice solely as a potential driver of economic gains.

This limited focus aside, these government-supported initiatives also appear to be oblivious to previous design-related government projects in Aotearoa. Design curator and historian Christopher Thompson has critiqued the Design Taskforce for completely ignoring the existence and overlapping work of its predecessor, the New Zealand Industrial Design Council (which had been abolished in the 1980s by an earlier Labour government). He writes, “By de-historicising its subject, the taskforce both proffered a vision of New Zealand design that had no past and asserted that this absence should be perceived as a positive attribute.”

This attitude valorises a concerning kind of anti-intellectualism in relation to design practice here. The design stories propagated by Better By Design mirror the type of myth-building that this article has suggested we should try to deflate in Aotearoa — a series of remarkable companies and company founders held up for inclusion in a vaulted national canon. The NZTE’s brochure for the Better by Design programme is an infantilised presentation of design as a nation-building exercise, almost devoid of meaningful content. It’s even called “The Book of Important Stuff.”

The opening pages of NZTE’s “Book of Important Stuff”

The opening pages of NZTE’s “Book of Important Stuff”

But there are hopeful stirrings, focused on this official realm. An alliance called DesignCo has recently come together to advocate for greater government support for design activity in Aotearoa — with goals that span tertiary education, research funding, and the integration of design processes into the public sector. The group was formed in 2012, when universities, the Designers Institute — and New Zealand Trade and Enterprise itself — worked on an unsuccessful bid for government funding to establish a Design Centre of Research Excellence.

Interestingly, their recently published PwC report, The Value of Design, adopts the language of economic development; its introduction by Massey’s Claire Robinson opening with the line, “There is a strong correlation between national prosperity, economic growth and a thriving design sector.” But the breadth of DesignCo’s goals, their stated aim of “elevating the role of design and designers,” and their assertion that design is fundamental to Aotearoa’s social and cultural, as well as economic, future, is reason to hope that they might advance a more sophisticated perception of what designers do and can contribute to everyday and civic life in Aotearoa.

I wanted to open this series by considering what’s at stake for design practice in Aotearoa — which we, as a small, already engaged community, are already invested in. Building understanding of the work that designers do, and the value it contributes to life in Aotearoa, depends on our ability to broaden our shared notion of what New Zealand design looks like, who it belongs to, and who can talk about it. This series will endeavour to look beyond inherited mythology, to map an expanded field of reference points and future possibilities for design and design-adjacent activities in Aotearoa. I hope you’ll follow along.