What is Design Thinking?

Written by Cameron Ralston

Supported by Creative New Zealand

Cameron Ralston is a contributor to Aotearoa Design Thinking 2017, a series of commissioned critical design essays published by Design Assembly and funded by Creative New Zealand.

This article is the first in a four part series which looks internally at this concept of ‘Design Thinking’ and what on earth that actually means. Is there really a designer-ly way of thinking? And what is relationship between thinking and designing? This series will attempt to clarify where we find ourselves in the current field of design.

Design — a hard thing to define, despite many attempts — is often described as a process or way of doing. Norman Potter in his 1969 book What is a designer argues that:

“Every human being is a designer. Many also earn their living by design – in every field that warrants pause, and careful consideration, between the conceiving of an action and a fashioning of the means to carry it out, and an estimation of its effects.” (1).

This view that design is linked to planning and is always preceded by something is further noted when he writes that design is, “distinguished from ‘making’ or from spontaneous activity.” (2). Interestingly Potter places fine-art and science on an aesthetic scale of sorts, the greater the aesthetic opportunity in design the closer to fine-art, and the further away from science. So it is recognised that design, as a field of visual communication, is connected to fine-art practice through a “visual sensibility” but separated by a complex network of specialisations, expertise and relationships.

Potter’s ideas have found their way to Aotearoa New Zealand as well. Max Hailstone’s 1985 book Design and Designers asks the same question of ‘what is a designer?’ He answers similarly to Potter:

“Design is a process. It is a process whereby a designer, equipped with a technical knowledge of all processes and materials available at the time, and a true understanding of the problems to be solved, and of the constraints that may be imposed upon the solution, together with a sensitive and humanitarian respect for the same, combines these different elements into a cohesive practical whole.” (3).

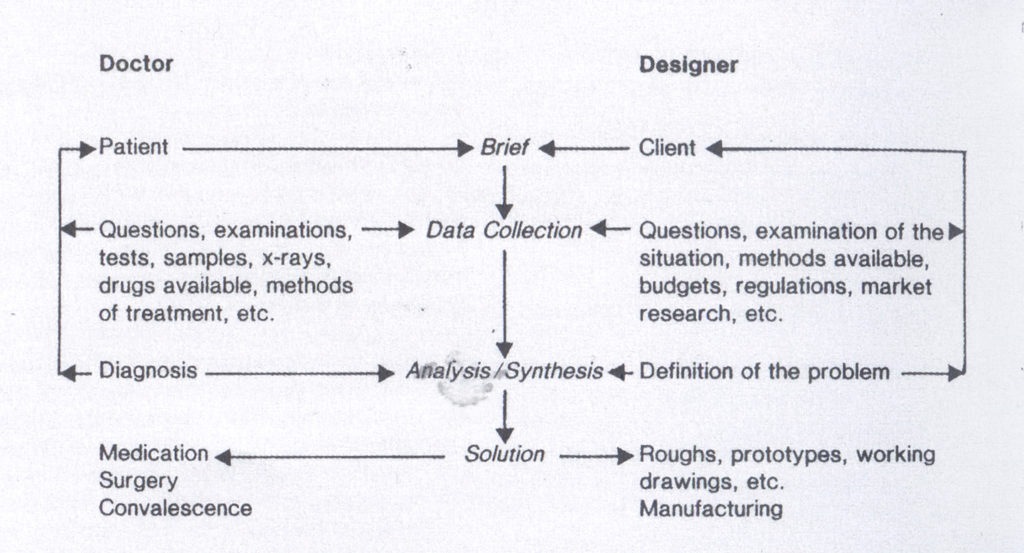

Diagram as it appears in Max Hailstone’s 1985 Design and Designers.

Both these definitions take design in the direction of science. The link to science is a way of attempting to give design an element of expertise, the trope of the doctor who solves problems is often used by both Potter and Hailstone. The designer is able to identify problems or questions, create a hypothesis, and the craft a solution. While these ideas have value, they are also cold and cerebral; and distant from the everyday practice of graphic design. New Zealand-based graphic designer and lecturer Jonty Valentine, in The National Grid #8 attempted to examine his own modernist tendency to want to differentiate design with its own bodies of knowledge:

“I realised that even though I had been talking about inter-disciplinary practice (maybe now inter-cultural discourse) for a while – I was still framing it with an inherently inward-looking Modernist attitude.” (4).

Valentine recognises the post-modern notion of de-differentiating cultural spheres but at the same time remains weary of the “denial of discreet or autonomous disciplinary knowledge”. Perhaps it’s worth thinking about through UK graphic designer, editor and writer Stuart Bailey’s endlessly quotable definition:

“…design only exists when other subjects exist first. It isn’t an A PRIORI discipline, but a GHOST; both a grey area and a meeting point – a contradiction in terms – or a node made visible only by plotting it through the lines of connections.”(5).

Bailey uses the A PRIORI to say that design doesn’t really have its own independent body of knowledge, and that it actually relies on other schools of thought to sustain itself.

At the As A___, I___ symposium held in Chicago, 2015, Charles Roderick of artist duo Hideous Beast said that although he makes work that is often using the material form of graphic design, it is the context and a particular set of questions he’s dealing with that are outside of graphic design which define the work. At one point he discussed a lesson he used with his art students at School of the Art Institute of Chicago by holding up a drink bottle and asking if it’s art? Despite it having aesthetic qualities that are traditionally associated with art the discourse has moved on significantly. Now the question is what is the piece’s place? And how does it find that? And there-in design is seen as being in service to something else — taking us back to the Stuart Bailey quote that, “…design only exists when other subjects exist first”. The design of the drink bottle is in service to practicality of drinking.

Charles Roderick talks about art, design and drink bottles at the As A ____,I ____ symposium.

So, then what happens to design objects when they are presented as art — as finished critical objects in and of themselves? One recent local example is Matthew Galloway’s Beyond Exhausted exhibition at The Physics Room. In this show, he exhibited reprinted issues of The Silver Bulletin alongside selected motifs and pieces which were discussed in the publications. Although initially a little jarring having design objects in the gallery, the exhibition was a play on the placement of arts and design in the ‘regeneration’ of Christchurch.

Installation shot Matthew Galloway’s Beyond Exhausted at the Physics Room.

One’s history of education and practice can also define where a work fits. Billy Apple for a long time has been making artworks that play with graphic design conventions of type and branding. Trained as an artist, his work sits comfortably in an art context while using tropes of commodification and branding.

In contrast to Apple and Galloway was South Island Poster Exhibition, an exhibition organised by Design Assembly held at XCHC Exchange Christchurch, in late 2016. The exhibition asked the audience to look at these posters from an aesthetic standpoint. Many were devoid of text or used graphic design in an abstract or literary sense. The underlying context of the works however was outside the gallery one example being Strategy Creative Christchurch studio’s poster for CoCA’s Vertigo Sea. This poster was also a recipient of a bronze DINZ Best Award and subsequently written about on the Design Assembly website. Whilst the Vertigo Sea poster is visually successful and works as a piece of graphic design it in itself feels out of place when removed from its purpose or service.

South Island Poster Exhibition featuring Strategy’s Vertigo Sea poster.

Artist Julia Morrison speaking at Arts Forum Christchurch spoke to this idea of work servicing something else. She felt public art in the city was being forced through a designer-ly process to meet certain urban planning goals:

“Inevitably there is a demand that an artwork must be of service to something other than art. (This) treats artists as designers, but artists are fundamentally and essentially proactive not reactive.”

She reasons that the decision making behind art is more free, and less concerned with returns, whereas design decision making is more tied to what will be gained (or solved) from the work made. The object here was almost irrelevant. This fairly limited interpretation of design is interesting to note as a desire to distance art from design thinking.

Julia Morrison speaking at Arts Forum Christchurch.

What does embracing design thinking look like then? The studio to latch itself onto design thinking the most in Christchurch is Strategy. Strategy sets itself into a problem-solving mould, listing ‘thinking’ as one of its five core processes alongside Assess, Create, Craft and Connect. The studio uses these to express to clients the services they offer:

“[Thinking] We capture the problem and the opportunities. We propose an answer that moves the brand forward and can deliver the results that you need.” (6).

They link into the language of business and commerce in order to show the value in the design process and design thinking. In Strategy’s thinking books there are reprints of articles published by Harvard Business School. Notably an article titled ‘Design Thinking’ by IDEO CEO and President Tim Brown was published in issue four. Brown argues for a strategic model of thinking whereby projects pass through three stages — inspiration, ideation and implementation. These are seen as steps towards innovation. He defines design thinking as:

“…a discipline that uses the designer’s sensibility and methods to match people’s needs with what is technologically feasible and what a viable business strategy can convert into customer value and market opportunity.” (7).

Strategy overlays such philosophies on their graphic design work. However, I would question how closely linked innovation and design are. Especially when design is often a process of research, editing and crafting.

Typographer and designer Alistair McCready in his article ‘Authors & Thinkers’ (8) pits ‘design as author’ and ‘design as thinker’ against one another. The author to him being more of an originator and the thinker being strategic and problem-solving. These two are actually part of the same thing; thinking is a part of making. McCready does however pick up on how our current society places the intellectual over the maker.

Berlin graphic designer Katja Gretzinger in her article ‘Thinking through Blind Spots’ notes the use of such definitions of processes is due to the necessity of being understood. She writes that:

“the discipline [of design] is situated almost exactly between subject and object… this intermediary position makes design a sort of precedent for theoretical inquiry. Yet simultaneously it makes the discipline quite susceptible to instrumentalisation, because the practice has to be interpreted—by the people involved in a design project.” (9).

Design thinking as a discipline could be seen as part of that instrumentalisation of design. Used as a tool for achieving a goal. Strategy treats design as a set of definable intellectual steps. Gretzinger writes that knowledge isn’t so easy to define.

“Knowledge is not just communicated through language, but also functions along more abstract lines; implicitly and subconsciously. This knowledge is neither visible nor quantifiable; it may be more like a pattern or layout that is distributed according to conventions. This distribution implements hierarchies, searches for differences, makes simplifications, represents power relations. Graphic designers work very closely with this knowledge. They make use of implicit social conventions in order to make information more easily understood.” (10).

Attempts to make design more formulaic and scientific have been made in order to communicate how design is made to those outside of the discipline. However perhaps like Gretzinger, it is more accurate to talk about design as a complex body of knowledge.

Can graphic design (as a field that is still figuring out its body of knowledge) have a critical discourse separate to art, literature, business and marketing? Short answer, yes. However, it is a strength of design that as a social discipline it is expanded by the fields it overlaps with. It can purposefully use different languages and guises in order to fulfil a specific function and reflect upon its methods.

If designers are looking for the enrichment and critical body of the discipline, we should be looking at this overlap. Already in this series Emma Ng has talked about the overlap of graphic design and political and Lana Lopesi on the publication as a curatorial space. Furthermore, by having critics independent but overlapping with the design industry we create opportunities to grow worthwhile criticism. These discussions don’t necessarily have to be read by the general public, but rather need an active and engaged community of readers, writers and designers to sustain it. It is through such efforts that discussion is brought about and design thinking can be brought closer to everyday design practice.

Design being an in-between discipline requires a knowledge and awareness of context. It seems natural that any definitions of design thinking that we take from this use that awareness at their core. Whether it be in service internally or externally the methods of distribution, applied bodies of thinking and placement of works can help locate a work. How a work takes these into account can often determine the success of it. It is natural that bodies of knowledge and thinking change and evolve. It is thus important that we keep asking designer-ly questions if we take creating a critical culture seriously.

(1): Norman Potter, What is a designer: things, places, messages, Hyphen Press, 2002, originally published 1969, p. 10.

(2): Ibid.

(3): Max Hailstone, ‘What is Design?’, Design and Designers, The Griffin Press and NZ Industrial Design Council, 1985.

(4): Jonty Valentine, ‘What is Design’, The National Grid #8, The National Grid, 2008, p. 94.

(5): Stuart Bailey, ‘Dear X’, Dot Dot Dot 8, Hague, The Netherlands, 2004, p. 3.

(6): Published in the final few pages of each issue of Strategy’s thinking books.

(7): Tim Brown, ‘Design Thinking’, published in thinking Issue Four, Strategy, p. 24

(8): Design Assembly: Field Guide 2016

(9): Katja Gretzinger, In a Manner of Reading Design, Sternberg Press, 2012, p. 165.

(10): Ibid, p. 166.

Love the article, I will be reading it many times, and sharing the link. My 2 cents worth is inspired from the last paragraph. Design Thinking for me is not only about educating those involved, creating a context and a unified process for all to understand, its about listening, synthesising, prototyping, refining and most importantly being seen to be ‘doing something’. The challenge is constantly communicating, maintaining and fitting into societies idea of what ‘work’ is. No matter if its a Concrete Cutter wanting to improve his business and Educational entity wanting to better a process or a Government Agency wanting to transform, us

‘Designer-ly Thinkers’ have to be able to articulate and tell stories to relate to all those involved. Its not all pretty.