Field Guide: JOHNNIE FREELAND – SYSTEMS NAVIGATOR

This Field Guide article sits within a series of commissioned essays, interviews, podcasts and artworks to be published over 16 weeks on designassembly.org.nz and culminate in a downloadable PDF publication which will be distributed nationally.

We are incredibly grateful to Creative New Zealand who funded this 2020 Field Guide, which actively investigates, celebrates, nurtures and challenges current design thinking, methodology and practitioners in the Aotearoa design community. The project is “a multidisciplinary exploration of New Zealand’s post-COVID design practice”. It is produced by five authors, six illustrators, with art direction, design, editorial, publishing and production support from the Design Assembly team & RUN Agency.

Supported by Creative New Zealand

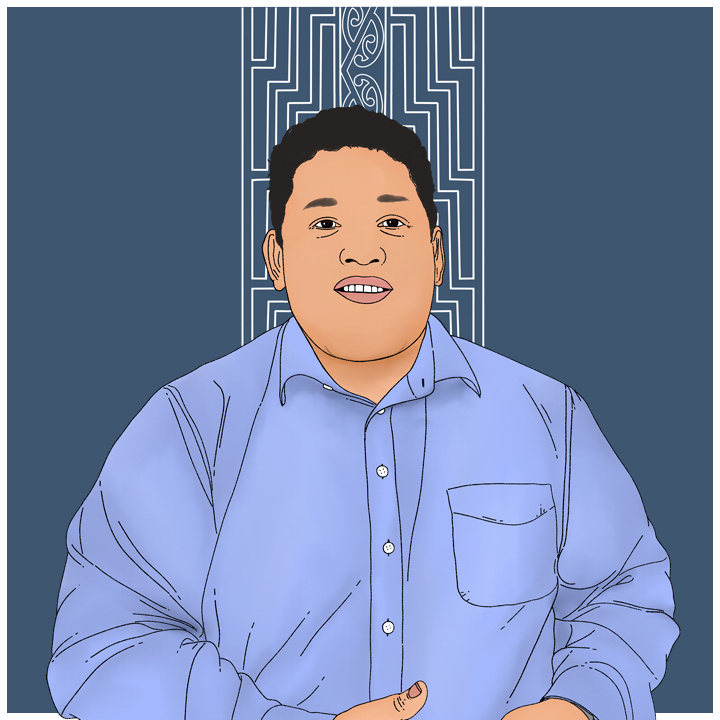

The artwork to accompany this essay is by Huriana Kopeke-Te Aho a Takatāpui artist based in Tāmaki Makaurau. Huriana is a self-taught illustrator and designer whose work is primarily influenced by their Māori whakapapa, takatāpui identity, and political beliefs. They have produced work for Action Station, Auckland Pride, Pantograph Punch, Rainbow Youth, RNZ, Re: News, Te Rau Ora and Waikato University among others. Their illustrations are also featured in Maui’s Taonga Tales/He Paki Taonga i a Māui and Protest Tautohetohe published through Te Papa Press.

JOHNNIE FREELAND – SYSTEMS NAVIGATOR

Desna Whaanga-Schollum & Mihi Tibble interview with Johnnie Freeland

Ngā mihi nunui! This article is the final in a series of tangata whenua article, looking at the ways that our people are drawing upon their ancestral knowledge and adapting the learnings to challenge the status quo.

‘Design-thinking skills are being employed in diverse fields of practice, weaving together tangata (people, community), te taiao (environment, place), wairua (spirit, intent) and mauri (energy, life-force). Moving beyond human-centred design, tangata whenua practitioners reference an eco-system of actors, and draw upon intergenerational knowledge. Social and cultural equity aims are served through the deployment of design tools.’[1]

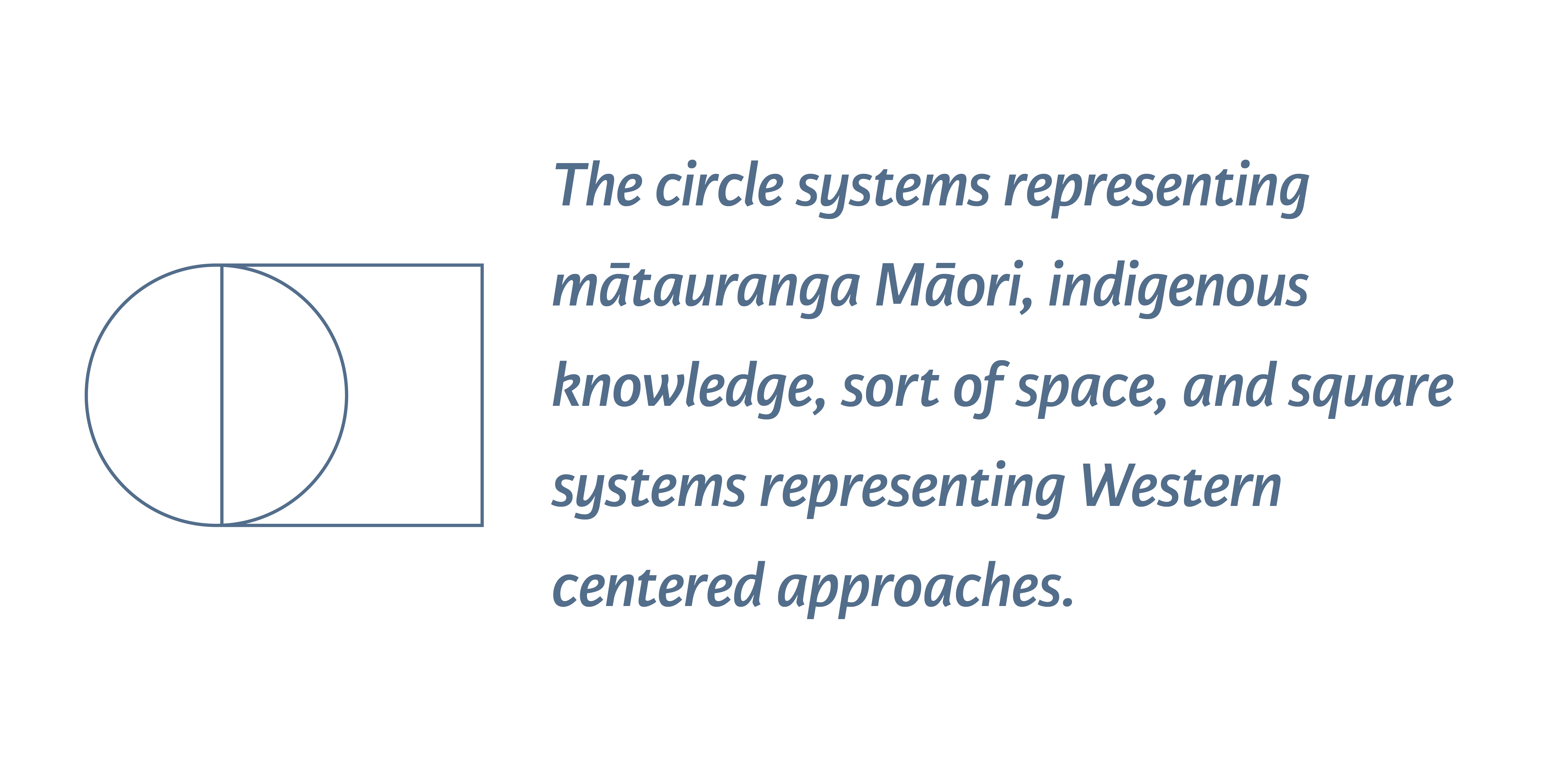

In this interview, Johnnie Freeland shares his groundbreaking systems-thinking navigation. Using the analogy of the square for Western knowledge systems, and the circle for Indigenous ways of thinking, doing, and being – mātauranga Māori – Johnnie goes deep. So be prepared to have your world-view challenged, rearranged, and re-envisioned. He brings an extremely pertinent way forward in these challengingly disjointed times, looking at how we might re-connect to ancestral knowledge navigation.

He rangi tā matawhāiti,

He rangi tā matawhānui.

A person with narrow vision

has a restricted horizon;

a person with wide vision

has plentiful opportunities.[2]

TIMATANGA // Introduction

Ko Matukutuureia te maunga.

Ko Te Maanuka te waiora.

Ko Ngaati Te Ata Waiohua te iwi.

Ko Johnnie Freeland tooku ingoa

Kia ora everybody, I want to talk about, my approach to how we navigate between what I call the square systems and circle systems. The circle systems representing mātauranga Māori, indigenous knowledge, sort of space, and square systems representing Western centered approaches. I call myself a Systems Navigator. And for the last 30 years, I’ve had the privilege of navigating in the space between spaces. In between mātauranga Māori [Māori knowledge systems] and Western systems primarily through a number of public sector roles for local government and central government. I find that space really exciting, but within that space, there’s a whole number of challenges around, as a mighty navigator, as a circle systems navigator. How do you ensure that you’re navigating to what I call your ‘true South’ direction, in a similar way that our tūpuna navigated from Hawaiiki[3] to Aotearoa. They used constellations like the Southern Cross as part of their bearing towards what I call a ‘true South’. Given that there is a magnetic South as well, and sometimes that pull of the magnetic South can pull us off course, in those situations we find ourselves often enclosed in a square system.

WHAKAPAPA // Layered, inter-connected knowledge systems

I frame a square system, and when we look at a square system, it’s whakapapa sits within Te Ao Uru – Western knowledge systems, and those are systems that have been imposed in this place, in Aotearoa, through the process of Colonization, Westernization and Urbanization. Often those systems are what I call ‘Human-Centered’. As opposed to a circle system, the indigenous systems that are centered around whakapapa. Not just human whakapapa, but our connections to whenua – place, tangata – our tūpuna (ancestors), mokopuna (following generations), relationships, and most importantly, our atua[4] relationships. And that is manifested in our whakapapa relationships across the natural environment.

So, in a circle system, it’s really understanding how we locate ourselves as humans within the context of the whakapapa of the universe. One of the interesting things in terms of square systems is that they actually don’t have whakapapa. They have a whakapapa in a sense of whakaaro[5], in theory, that has come from a human experience. Often in that context, that it’s almost man sits above nature, man tries to control nature. That’s the key distinction between a square system and a circle system.

As kaimahi [practitioners/workers] Māori within square systems, sometimes it’s challenging to find how we locate ourselves in either system. Because sometimes we think we might be operating in a circle way, when we sort of zoom out, we actually find that we are still operating within a square system. In exploring what a circle system looks like or a circle approach – what I want to sort of start with, is almost looking at that real DNA cellular level. Because the whakaaro is our DNA is made up of star dust, and that’s proven in modern physics, and astrophysics context. Our tūpuna already knew that we were part of the universe that’s in our DNA. Western systems and Western science, finally, have got the technology to actually prove that, actually reinforce what our tūpuna already knew. So within that context, what I look to see is the fundamental electrons, protons, if you like. Those symbiotic interconnected relationships between ‘Mana’[6], ‘Tapu’ and ‘Mauri’, and they’re woven together through ‘Te Ha’, the life breath that holds. And whether it’s at a cellular level, at a planetary level, those are the fundamental building blocks of the universe. We share that with water, with other domains of our atua in terms of Tāne[7], Tangaroa[8]. So when we look at it in a whakapapa centered way, we are really looking to reconnect and engage in that whakapapa context.

It’s really important how we locate ourselves as humans – in terms of the whakapapa of the universe, humanity sit, in one little corner, and in the context of that whakapapa, we sit in a teina [junior] relationship.

TE TAIAO // Environment, Place, Reconnecting, Repatriating and Regenerating

One of the awesome things about circle systems, around mātauranga Māori or Māori knowledge – is that Māori knowledge is a combination of the inherited DNA around practice, and ultimately, all that knowledge actually sits in nature. One of the things that demonstrates how wise our tūpuna were, they’ve left us a coding of unlocking that knowledge in waiata [song], in karakia [ritual chants], in pūrākau [ancestral legends, stories] and if you like there’s a Da Vinci Code, they left in that. Due to the impact of square systems, some of that coding has been fragmented, and what’s exciting, is that as a people we’re looking to repatriate and reconnect the code.

Some of that code actually sits with other indigenous people throughout the world. One of the best examples, if we look at the regeneration in the restoration of waka voyaging and navigation, is that ourselves together with Hawaiians and others throughout the Pacific, got to reconnect to where that knowledge sat in the South Pacific, in Southeast Asia. Through that knowledge and through a tohunga [expert knowledge holder] called Pius ‘Mau’ [Piailug][9], we’re able to re-impart that knowledge. Our people went and re-practiced that, and for the last 30 years, we’ve had this massive regeneration of waka voyaging. In essence, they’ve been able to recapture the ‘Da Vinci Code’, and the knowledge and things that were framed as myths, actually were navigation or coordinates and stories which are being used today to reaffirm and recapture that knowledge.

What’s important about our repatriation of our own whakapapa based knowledge, is really around re-instilling confidence and self-belief in who we are. Because one of the biggest impacts and effects of things like colonization, is that its undermined our own belief in who we are, and our own systems, we’ve sort of lost confidence in that. So what’s really exciting is rebuilding, reestablishing that confidence and that belief and trust in that knowledge. Actually, it’s almost like a reunion of sorts, where we are reconnecting, repatriating and regenerating our own whakapapa.

One of the most important things is how we look to actively practice, connect, engage with those whakapapa domains around us. Because as we look to undertake that hononga – or that connection, and engagement – that information, that knowledge starts to reveal itself in systems. Whether it’s waka navigation or maramataka [Māori lunar calendar], real important tools to help us reconnect, recalibrate and through that hononga, through what I call whakapapatanga, the reestablishing of those whakapapa relationships. I think one of the most important things is the rediscovery of Māori time, which is actually a real positive thing, in terms of what we mean by ‘te wā’, and that’s really about the convergence of time and space, where our tūpuna, ourselves and our mokopuna can actually sit together.

MAURI // Energy, Life-force

But one of the key things when we think about that navigating that space between circle systems and square systems, is actually why and what you’re wanting to achieve. And for me, the key, especially when we’re in the mahi oranga – of enabling the well-being of whanau – it centers around your role in helping transform the state of being, and for me, is a transformational whānau. Given the effects and impacts of colonization and Westernization and urbanization, we’re dealing in ‘how do we transform the state of being for our people, with our people’, which is the most important thing. From a state of mauri-noho mauri-mate[10] [poor health], to a state of mauri-tū mauri-ora [well-being]. That’s what really excites me around the whakaaro of te whai oranga – or the pursuit of well-being – te pai oranga – which is really about how do we navigate the horizon of well-being, and how do we equip ourselves but also our whānau with the tools to navigate that space.

In a similar way, the way our tūpuna, voyaged from Hawaiiki to Aotearoa. Part of that is understanding the context of why they needed to migrate, transform their space from Hawaiiki. What was the state of Hawaiiki at that time for them? For me, when you listen to some of our traditions, it was a state of mauri-noho mauri-mate, and what they were pursuing in their voyage to Aotearoa, was a whai oranga pathway to get to mauri-tu mauri-ora. So being able to use our system because what we shared really around the state of oranga, is relative to the state of mana, mauri and tapu. If we can evoke that sense of oranga, with our whānau, then we actually are helping them to navigate, transforming that state of being.

In terms of how we navigate that space, in terms of pursuing oranga, the question then is, what role do we play within that as practitioners, as guides as healers. One of the things is, again looking to our waka knowledge, and thinking that often in a square system, it focuses on the role of the captain, the leader, who is that person that is accountable. That’s a real counter to a circle systems approach when, in a Māori context, we talk about triangulation in the practice of leadership. That doesn’t sit on one person, that actually sits in a number of people, and our whānau sit at the heart. So within that context, we think about the Kaiārahi [guide] role, and the role of the Kaiārahi in terms of helping weave the kaupapa and the people together. But then that’s complemented by the Kaiwhakatere role, the role of the Navigator, and their role was to help navigate the waka journey to that state of well-being. Then the other bit, is what we call the Kaiurungi – the steering, who helps steer the waka along that pathway. And ideally, whānau should be steering the waka. If it’s about whānau lead, whānau driven oranga, then our role is to help wrap around that, and equip them with the tools, the confidence. Because one of the key whakairo, is whānau are the primary health givers in terms of tipuna, and mokopuna. So we need to think about it in the intergenerational context and terms of what whakapapa speaks to.

WERO // The Challenge for healers, knowledge navigators, designers

So for me, the state of oranga – well-being – for our people actually sits in the heart of the circle. One of our challenges as Māori healers, Māori navigators, Kaimahi, within square oranga systems, how do we help navigate our people back to the circle? One of the whakaaro that sort of unfolded for me over the last couple of years, is a focus on how do we re-circle-ize ourselves. What that means is that while there’s been an imposition of square systems, the circle has always been there, it’s just become unfocused in a sense in the square has dominated that view. Within that the circle actually sits in our whakapapa relationships with nature, with taiao, and with our atua.

So how do we look to re-circle-ize ourselves? One of those sort of controversial things is, I see that re-circle-ization as a pathway, more important than decolonization if I could use that term. For me, decolonization requires a whole lot of effort in sort of deconstructing the square. Like our tūpuna, when Western knowledge first arrived here, their circle was a given. They were able to take that square technology and operate it within a circle system. Up until the squares started to undermine the circle where we are, in our predicament today. That’s one of the key whakaaro I want to leave around just that, thinking about what re-circle-ization looks like.

My little fear around decolonization is it may lead to a point, where we start to deconstruct, or decolonize our own DNA. For me, who am I to question my tūpuna in their decisions, why they had hononga [connections] with that with my tūpuna from Scotland, from Ireland, who makes up my DNA today. That’s a place for me I don’t really want to go to. But certainly, where the big opportunity for us, for me is, actually sits in the circle.

In terms of my concluding whakaaro, I just want to leave us with a question, a challenge. In a truly to us as mana whenua, as tangata whenua, as iwi taketake[11], as indigenous peoples, and really thinking about the challenge of how we re-circle-ize our minds, understand our symbiotic whakapapa, our relationships to nature, to the universe to each other, and to this place, of Aotearoa, place of Tāmaki Makaurau, wherever our wahi [location] is. How we look to, I guess, in that pursuit oranga, in the real shift sits between that of our greater sense of self, which looks like a shift from ‘me’ to ‘we’. That’s our biggest challenge. That’s a space that our tūpuna operated in terms of their understanding of our place within our whānau, but also our place within the universe, and our place within the landscape. We’ve become a little bit disconnected and displaced by square systems, knowledge systems. How do we pursue and relocate ourselves back to the circle.

One critical thing is that our whai oranga pathway, actually sits in mātauranga Māori, built through observation and reflection, and actually real practice. We’ve got to get out there and connect and engage with whakapapa in the everyday sense. And how do we enable whānau to do that? Because in that daily practice, in that seasonal practice, in that yearly practice, is actually the pathway to our oranga. The real key thing is how we grow our competence and confidence, and that reaffirmation of our own belief in who we are, the belief in the values that those myths, so-called myths, are actually truths. By anchoring ourselves, relocating ourselves back into that space, how it can then guide, define, and inform everything we do. And in so doing, we are invoking that state of oranga.

Kia ora Tātou, Mauri Tū, Mauri Ora.

Johnnie Freeland: https://www.linkedin.com/in/johnnie-freeland/

[1] Whaanga-Schollum, D. DESIGNING MĀORI FUTURES – SYSTEMS DISRUPTION. Design Assembly Field Guide series. 2020.

[2] Alsop, P & Kupenga, Te Rau, ‘Mauri Ora. Wisdom from the Māori World’. Potton & Burton, 2014

[3] Hawaiiki: https://teara.govt.nz/en/hawaiki/page-1

[4] “Ancestor with continuing influence, god, demon, supernatural being, deity, ghost, object of superstitious regard, strange being – although often translated as ‘god’ and now also used for the Christian God, this is a misconception of the real meaning. Many Māori trace their ancestry from atua in their whakapapa and they are regarded as ancestors with influence over particular domains. These atua also were a way of rationalising and perceiving the world. Normally invisible, atua may have visible representations.” www.maoridictionary.co.nz

[5] To think, plan, consider, decide. www.maoridictionary.co.nz

[6] For mana, tapu and mauri, see: https://teara.govt.nz/en/te-ao-marama-the-natural-world/page-5

[7] Tāne: https://teara.govt.nz/en/te-waonui-a-tane-forest-mythology/page-1

[8] Tangaroa: https://teara.govt.nz/en/tangaroa-the-sea

[9] Pius “Mau” Piailug (932 – July 12, 2010) was a Micronesian navigator from the Carolinian island of Satawal, best known as a teacher of traditional, non-instrument wayfinding methods for open-ocean voyaging. Mau’s Carolinian navigation system, which relies on navigational clues using the Sun and stars, winds and clouds, seas and swells, and birds and fish, was acquired through rote learning passed down through teachings in the oral tradition. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mau_Piailug

[10] Durie discusses Mauri states: https://poutamapounamu.org.nz/mauri-ora/ako-critical-contexts-for-change

[11] long-established, original, ancient, own, lasting, aboriginal, native, indigenous. www.maoridictionary.