A man you need to know: Robert Coupland Harding, Part IV

Written by Kelly Gilchrist

Earlier articles in this series are available here: Part I, Part II, Part III

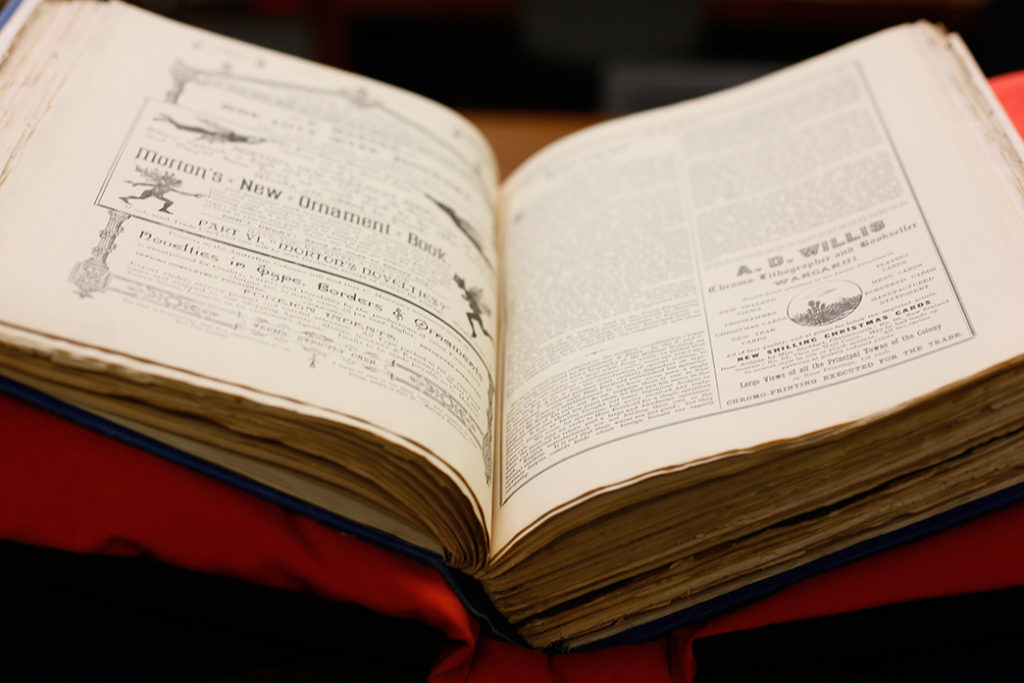

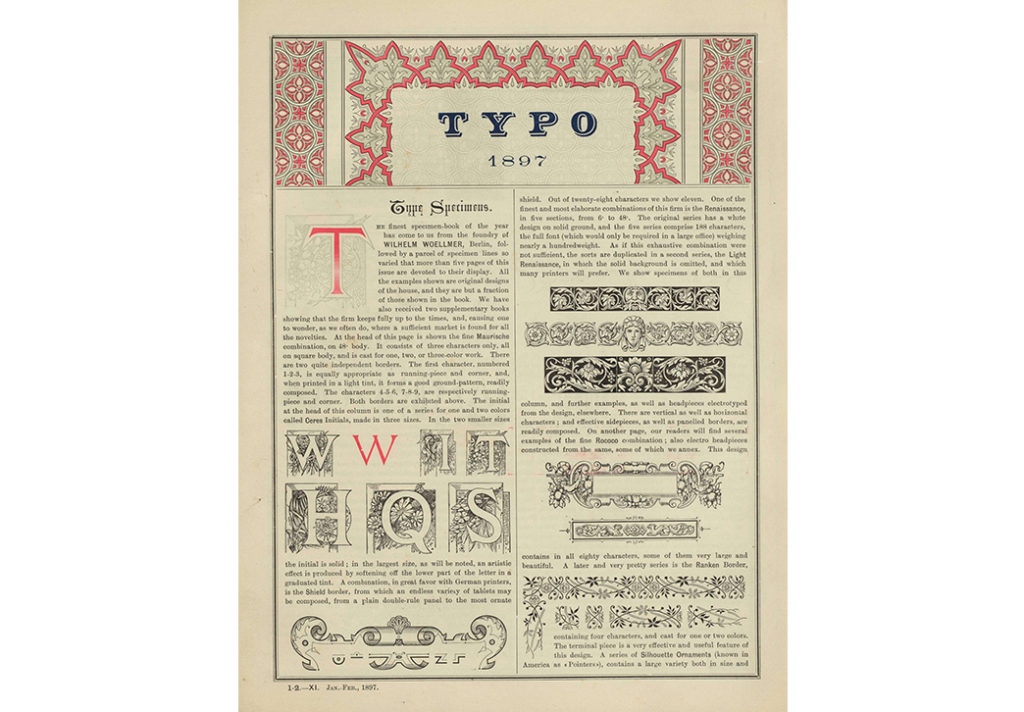

To undertake a project the size of Typo is an outstanding feat by today’s standard; to produce an eight to twelve page, detailed, comprehensive, virtually error free, journal, essentially single-handedly every month; Robert Coupland Harding was a workaholic. He was a clear optimist and infatuated with typography. He simultaneously operated a printing business, lead typographical associations, and published an international journal. He raised Typo in a young and small colony a great distance from the rest of the world. Harding succeeded in placing New Zealand as a contender of international printing standards. He endeavoured to achieve what other journals had failed to do and had created a prized procession for the people in the printing and associated industries. It is unknown how many subscribers Typo had, although, we do know that the journal travelled far and wide including many of the international foundries who received a complimentary copy in return for their type specimen. Regrettably, Harding’s obsession with Typo was ultimately the death of the journal. As time went on fewer foundries and printers paid for their copy of Typo, which understandably left Harding in financial trouble. Despite his obsessions and inadequate legacy, he remains a prominent figure in New Zealand’s design history: a man you need to know.

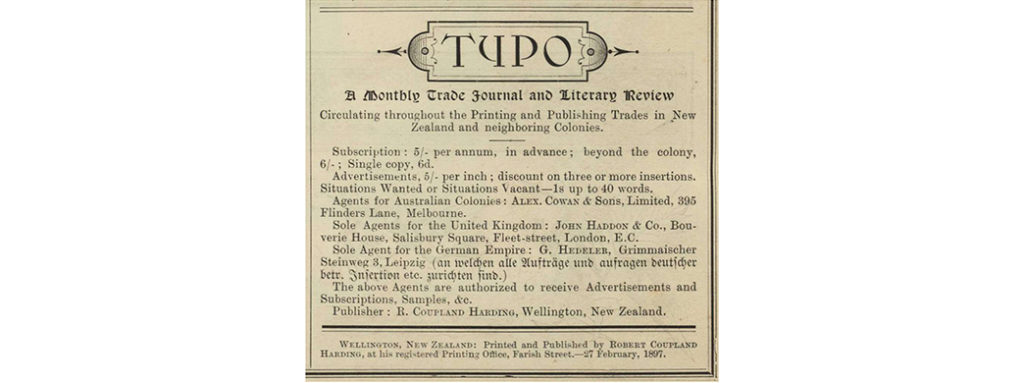

A broke and, eventually unemployed, Harding found it difficult to continue his unprofitable one man band project. Typo eventually, similar to current magazines, became littered with advertisements for foundries, bookbinders and new technologies. These advertisements were the result of necessary profit in order to continue his expensive brainchild. According to the printed signatures on the final page of Typo, Harding moved to Wellington in June 1890, in the hope to restore his business. Unfortunately, the move to Wellington was unsuccessful, despite his remarkable knowledge and skill in artistic typography, he no longer had a place in a world of global industrialisation. This new world had new machinery, technology that could achieve what men had once done but faster and cheaper. The consistency of Typo’s issues slowly faded, by 1892, Harding only released eight issues of the usual twelve, by 1893 three annual issues, by 1894, one. Between February 1894 and January 1897, there were no new issues of Typo. After a few unsuccessful business partnerships, Harding was hired by the Government Printing Office, as a compositor and then worked for The Evening Post as a reviewer and reader. In the end, Harding’s final issue of Typo, the 27th February, 1897 – was without a note or a farewell – he simply continued to ask for subscriptions.

Although, he had ended Typo, Harding continued to collect and trade print material. He remained a prominent figure in colonial print until his death in 1916. Harding’s legacy as a knowledgeable and skilled printer was remembered by The Evening Post as:

One of the ablest native-born printers and journalists in the Dominion … simply revelled in intricate and difficult typography … his store of knowledge on remarkably wide range of subjects made him a colleague of exceptional value. His versatility was, indeed remarkable.

And The Triad, a leading nineteenth century arts magazine, writes:

Mr Harding’s knowledge of type and all connected with it was certainly profound, and up to recently, he was in regular correspondence with type founders in Leipsic (the home of printing), London Paris and New York. With bookbinders and printers like Zaehsdorf and the De Vinnes, he was on intimate terms.

Harding’s teachings on typography are the clear central element of his legacy, nevertheless, Typo, provides a unique historical perspective. His viewpoint on Māori culture and language and his discussions on ‘the old New Zealand,’ provide interesting reading. In an article titled, Old and New, Harding discusses the departure of worthy pioneers from colonial New Zealand, he writes:

Old New Zealand is passing away. Its beautiful and characteristic fauna and flora are fast disappearing and giving place to alien forms; its native inhabitants are rapidly diminishing, and with them perish their language and traditions. But far greater loss than these—the worthy pioneers who laid firmly and well the foundations of civilization and liberty in these islands, have mostly departed for ever, and the residue are following fast. Who is to take their place?

He encourages ‘Young New Zealand’ to step up and take on the responsibilities to develop this nation. Harding held many volumes on Māori culture and language in his library collection. His self-proclaimed mentor, William Colenso, who printed the first Māori bible and the Treaty of Waitangi, perhaps sparked Harding’s interest in the language and culture. Harding retained more than a passing linguistic interested in the construction, visual display and the future of the language, he printed a Māori newspaper and often mentioned the language throughout Typo. Harding reviews his disgust of the Māori language missing from a pamphlet received from A. B. Fleming & Co. printers of Edinburgh:

send us a finely-printed quarto pamphlet, with descriptions and illustrations of their extensive works, and advertisements of their wares in many languages — not excepting the Maori!

This is perhaps a small and short contribution to the memory of Robert Coupland Harding, although, 130 years on since the first issue of Typo, I write this to continue his memory and legacy. The monthly typographically packed eight to twelve page journal on 182 x 284mm paper, was the pinnacle of Harding’s career and a honoured piece of New Zealand design history. Perhaps there is a reason the design history of New Zealand has become a small part of the twenty-first century design industry and education. Ultimately, there may be multiple reasons, although, we cannot unconsciously lose a part of us or of design.

This sees the end of Harding’s story. If you want to know more feel free to get in touch through my website www.kellygilchristdesign.com. Next I intend to write a series of four new articles for the rest of 2017. You can find the digitalised pages of Typo on Victoria University NZETC by clicking here. And original copies of Typo in the Sir George Grey Collections, Auckland Central Library and the National Library of New Zealand, Wellington.

Kelly Gilchrist is a graphic designer (recently turned writer) with a fondness for the ‘old’. This drives her personal interest in history, typography, and books. Better with the handmade, Kelly’s expensive pastimes include book binding, letterpress printing, analogue photography and paper engineering. She is currently studying an Honours degree at AUT University and is also part of the Photography Collections team at the Auckland War Memorial Museum, in order to digitalise the entire museum collection.